It is time to Unbundle

A framework for survival

Today’s piece focuses on how start-ups would differentiate themselves in a sea of randoms through specialising in niches and building sticky communities. Today’s sponsor is a venture that does exactly that. They are the talent on-ramp for developers looking to transition to Web3 and the folks behind EthIndia. The last iteration of their hackathon in Bengaluru attracted 20,0000 applicants and 461 project submissions.

Over 250k developers are a part of Devfolio today. They have given out over $2.5 million in bounties to developers trying to get their proof-of-concepts alive. They are in the process of rolling out a credentialing system for developers in the months to come. Stay in sync with all things Web3 development related by following their Twitter here.

Hello!

My last piece was intended as a form of closure – an admission of all the dumb things the digital assets space did and the reasoning behind why we did them. It was also my shot at determining what may be next for the industry. It resonated with many of you.

With that out of the way, I am laying out a few frameworks for what may be next for startups and VCs in the industry. It is based on a mental model I use to think about which businesses may take off during the depths of a bear market. The kind I would like to spend time on over the coming quarters.

In March of 2022, I wrote about aggregation theory and its application to Web3. The core of the thesis was that blockchains would collapse the cost of verification and trust. This would make it possible for a new generation of businesses to be built and scaled at a pace that was impossible before. Think of OpenSea. There is no team verifying if each Bored Ape sold on the platform is an original. There are no concerns about duplicate assets being transacted as long as the right smart contracts are involved.

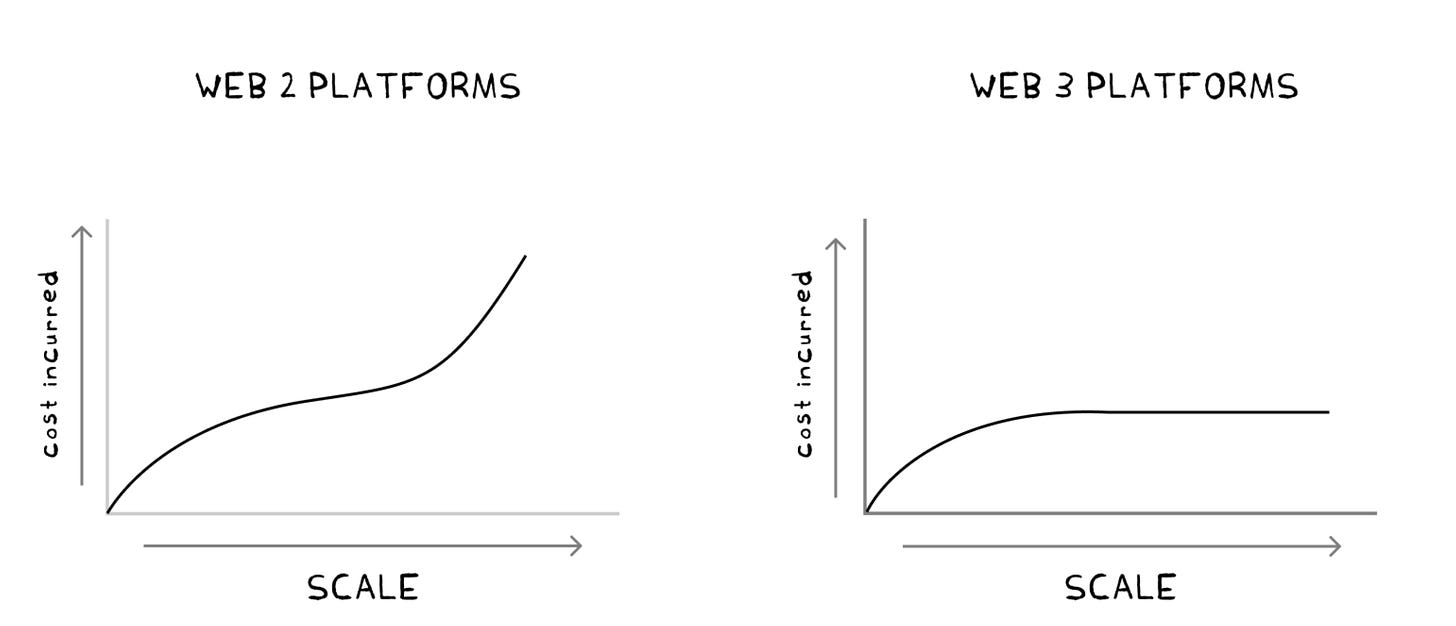

In traditional markets like Amazon, or Facebook’s ad marketplaces, the marginal cost for each new market interaction rises as more users come to the platform. Because the possibility of fraud is high. Even in digital consumption goods like streaming music (on Spotify) or the sale of in-game items through Steam, marginal costs increase with rising count of users. The kind of fraud checks you do when a platform has ten thousand users is distinctly different from what a platform with a million users will require. Blockchains tend to collapse that cost to zero.

The graphs above indicate the costs on typical internet-native platforms over the last decade. First, there is an initial build-up of cost for hiring, development and acquiring users. Costs then flatline as existing processes onboard an increasing count of users. Finally, burn accelerates once a critical mass is reached to maintain relative market share.

In the case of Web3 platforms like Uniswap, the initial cost is in terms of code deployments and audits. The users bear the cost of adding liquidity to pools. So there is no marginal cost addition as the platform scales. Blockchain-linked dApps are unique because the marginal cost (to the venture) tends to stay flat regardless of how many millions of transactions occur.

However, there is a risk that comes with building blockchain-first applications. And that is liquidity. Most emergent ventures are fighting for one of two resources. One is attention. And the other is capital. Traditional web2 media platforms hacked into your minds or wallets through strong network effects. Once their user bases hit a critical mass, people were practically forced to sign up for platforms like Facebook or WhatsApp because the cost of not participating was missing out on essential updates or events. Those platforms became the town squares where everything happened. The literal gateways to civilisation (and its eventual collapse.)

But the reason why firms like Meta could build this liquidity of attention was the ease with which users could sign onto them. (I use the term “liquidity” to loosely refer to the number of human hours spent on a product on a given day). WhatsApp, for instance, barely required people to have an email address to join. This played a crucial role in emerging markets like India, where phone numbers were the only form of digital identity users had.

Similarly, Instagram tapped into existing behavioural patterns when the platform took off. People were accustomed to taking images of their day-to-day activities. Instagram only made the process easier. It’s not rocket science to tap into our human tendency to talk frequently or our insatiable appetite for vanity. (In hindsight)

Private Keys, Public Problems

Contrast this with Web3 applications today. There’s a complex maze of switching chains, wallets and web interfaces before users get what they want. This is fine if you target a niche subset willing to endure pain for lack of alternatives. Stablecoins, for instance, provide a massively better user experience than banks with slow processing times in emerging markets.

But the story changes if you want to scale to tens of millions of users as a venture. The challenge most dApps have today is that they are competing for mindshare in a fragmented ecosystem that barely sees ~10% of the internet’s user base on it today.

Pundits often argue that dApps today appeal only to users with an appetite for volatility and risk. And that may indeed be true, but this reflexivity works in two ways. When prices trend upward, people pile on to the same trade en-masse. Shiba-Inu tokens make up for ~7 to 8% of the exchange balances of some Indian exchanges.

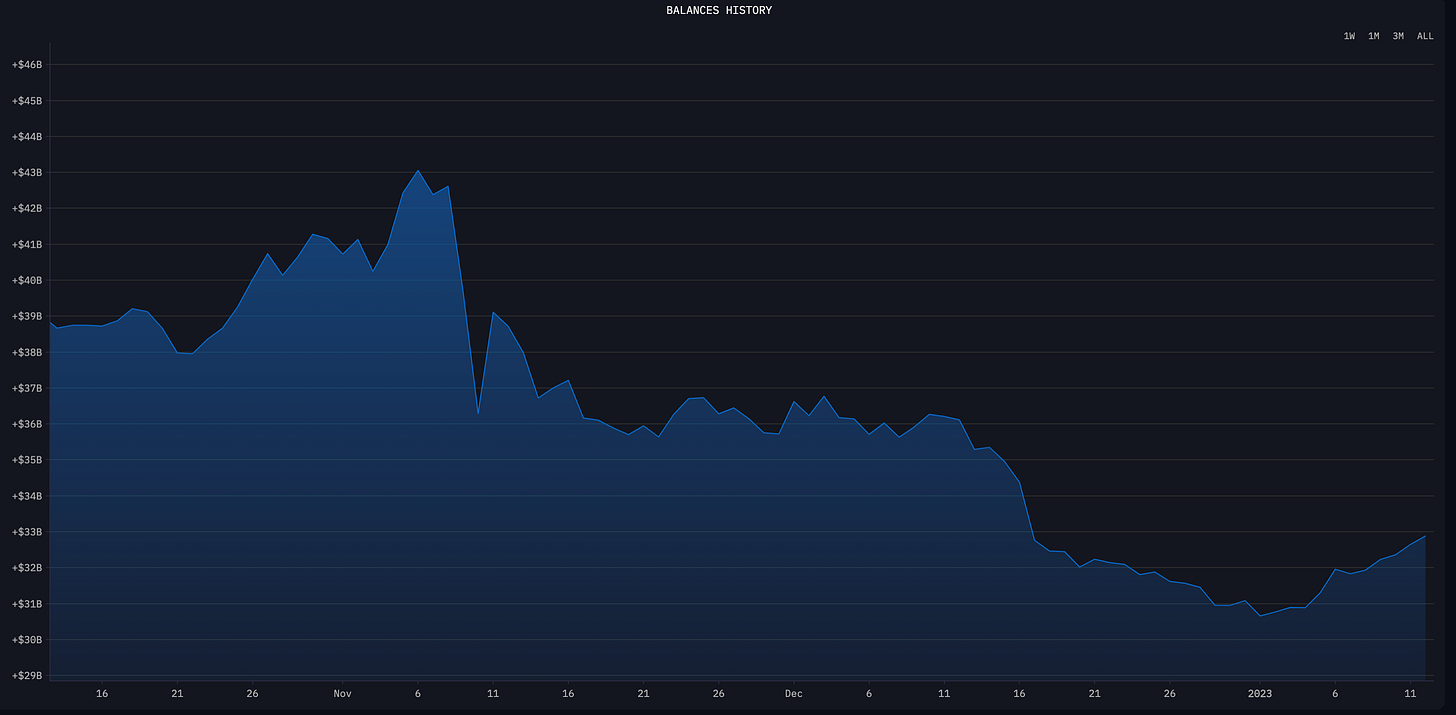

When the markets collapse, people lose money and leave the industry altogether. Overly-volatile consumer-facing apps do not have the consumer’s best interest in mind and are not sustainable in bear markets. The speculatory frenzy hard-wired into these products are temporary hacks that enriches random token holders.

The death knell for dApps would be to ignore how easy capital flight is in the context of digital assets. For scale, Binance saw $3 billion flow out of their balances in 24 hours. A bear market like the one we are in right now can kill startups through consumer apathy before a hack or lack of venture funding does it.

Web3 ventures often struggle to attract sufficient users to kickstart network effects that come with a large user base. In the absence of users, founders tend to add more features. They think an added engineer or a few more sales hires will fix their problems. Key hires are made at high expenses. Burn rates increase, and the venture has to shut shop with no PMF a few months later.

Sometimes, what kills startups is not a lack of features or a broken sales pipeline. It’s simply, people not caring enough about what the product offers. Apathy kills.

Battling Apathy

Markets are a pendulum that swings between periods of excitement and apathy. Bull and bear cycles are quantitative measures of human sentiment. But there’s a different way market cycles play out: between periods of bundling and unbundling. Both are after-effects of swings in consumer attention. Let me explain.

Aggregation theory suggests that bringing together large user bases reduces the cost of distribution, enabling newer business models like OpenSea. Unbundling sits at the polar opposite of what happens with Aggregation theory. A period where, founders switch to focusing on niche verticals with sticky user bases instead of obsessing over scaling user count during market apathy.

Distribution costs increase when you have a small user base. This means startups need to be able to extract more dollars per user if they hope to survive a bear market. (CAC vs LTV in Silicon Valley speak). The way to ensure every user adds to your top-line is by stripping away all the “nice to have” bits in a product and obsessing over a few things that meet existing consumer needs. By obsessing about the handful of customers that are willing to pay, here and now.

The evolution of the internet has several examples of this. Amazon upended commerce as we know it, but it started with an obsession for helping nerds buy books online. Facebook? Sure it can be used to overthrow governments and spread propaganda today, but its initial use case was allowing kids in the Ivy League to rate their classmates. Netflix? They have a production budget larger than India’s education budget today, but they simply focused on delivering DVDs to houses when they started. Do you see where I’m going with this?

There’s a reason why this occurs. Products that focus on a singular pain point stand out more quickly. Firms reduce burn when they focus on only a tiny feature subset. And when something is simple, customer acquisition happens organically. These are phases of rapid product iteration as power users vocalise which “nice to haves’ they’d like to see added to the product over time.

This played out during the last few bear cycles. During their earliest days, Nansen focused on allowing users to track wallets and token transfers. They have since expanded to DAOs, NFTs and the multi-chain world. Binance began as a place to spot-trade altcoins. They have since expanded to a parallel economy that supports everything from derivatives to P2P on-ramps and gaming. Finally, CoinMarketcap and CoinGecko started as platforms that merely offered token prices. Head to CoinGecko today, and you will see how they have expanded to a trading terminal, a portfolio manager, a research hub and an API provider over due course. See a trend?

A handful of DeFi ventures have pursued the same strategy. Curve, for instance, started as an automated market maker focused exclusively on stablecoins. The AMM-based exchange became one of the best places to trade millions worth of stablecoins from one to another. The slippage sometimes beats what even centralised platforms like FTX could offer. By focusing on a specific vertical, they avoided going head-on against Uniswap, which was expanding to a long tail of unlisted assets.

But do these ventures (or dApps) stay unbundled? Not really. Once a critical mass of liquidity – either attention or capital – enters the product, teams may add feature subsets to better retain users within their ecosystem. Take Aave, who started with lending-as-a-product long back when maybe five credible players were pursuing the opportunity. They have since integrated the ability to swap between assets within their interface. As of August 2022, they planned to release their stablecoin in the market.

Unbundling is an effort towards, in Paul Graham’s words, doing things that don’t scale. It is the pursuit of a niche few customers underserved by the incumbents. A calculated curation of a handful of users with nowhere else to go for the specific problem a venture solves. Unbundling unlocks entirely new customer bases with few competing counterparties. It changes the unit economics for early-stage ventures. A lower cost of acquiring users means a faster pathway to profitability—or more opportunities to iterate till you find PMF.

Levers of Unbundling

Nothing I said so far is rocket science. It is common sense that founders should reduce CACs and focus on building tools that matter. All I did so far was to give a mental model and instances of how unbundling played out in the past. But if you were to think, okay, I should focus on unbundling what I’m building as I don’t have any PMF, how would you go about doing that?

Founders can unbundle products by focusing on crucial feature subsets that blockchains enable. If you are a founder, it may help to determine whether focusing on a single feature subset in your product brings out any of these characteristics, as they may help you build a moat in a sea of replicas. Each of these levers simply tie back to what I said initially – all startups compete for attention, or capital.

Capital Efficiency

I believe unbundling in the context of capital-intensive startups (like the ones in DeFi) will happen by making products capital efficient. The underlying thesis is that consumers flow towards markets that cost the lowest. If you can iterate on a feature sufficiently enough to collapse cost, it will bring in users.

I use “capital efficiency” as a measure – of the amount of money (TVL) required by a venture to scale without bottlenecks. You have a liability machine if bringing in $100 million in volume needs $1 billion in user deposits. Providing incentives in the form of tokens can source capital from users, but it still means the venture is exposed to hacks on their smart contracts.

There are a few examples of this in the wild. For example, products like 0x Matcha and Hashflow focus on protecting consumers from MEV (miner-extractable value) by taking quotes directly from market-makers. As a result, they can offer better quotes than Binance for large orders on converting Ethereum to USDC, even though centralisation risks are at play.

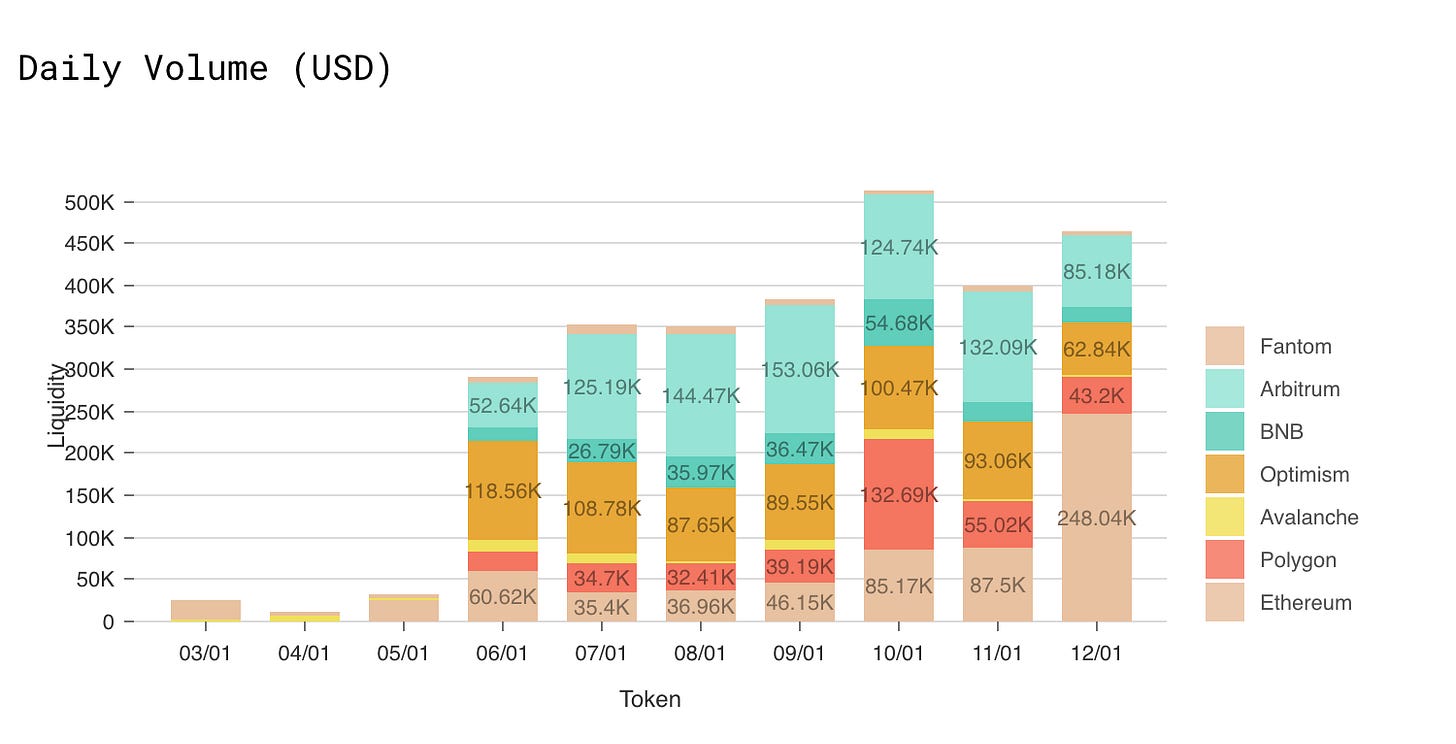

Hashflow has done close to $12 billion in cumulative by being the best place for converting a limited number of assets. Uniswap, in contrast, pursues the long tail of smaller altcoins on their automated market-maker model.

There’s a variation of this at play with blockchain bridges too. There’s ample evidence through multiple hacks suggesting that holding billions of dollars in smart contracts for bridges may not be a good idea. There are alternatives in the wild. For example, Biconomy’s Hyphen has enabled $178 million dollars in volume bridged for over 54,000 users with a mere $3 million locked in their smart contracts.

What about lending? Surely, parking billions of dollars in protocols that pay yields lower than what a bank account provide does not sound sensible. But it is where we are as the appetite for borrowing is generally less during periods of low volatility. If a large amount of capital provided for lending is sitting idle, protocol yield will decline.

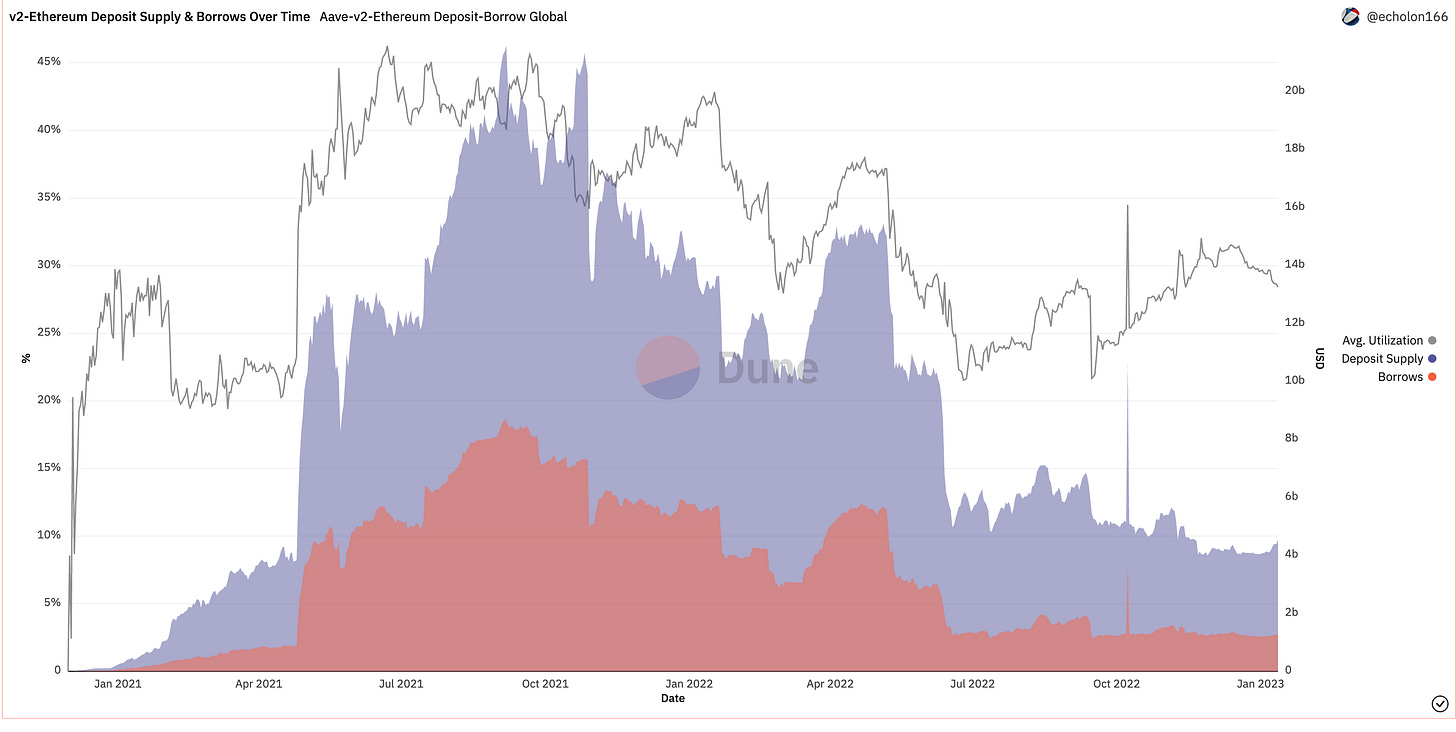

One metric used to measure this is the average utilisation ratio. It is defined as the amount of borrows, divided by the total capital deposited. On a platform like Aave – it has averaged around ~30% over the last few years.

Newer primitives like Gearbox have a utilisation ratio as high as 70%. Granted, this is an apples-to-oranges comparison as one is a lending product and the other offers margin, the ability to offer yield for larger pools of capital will begin to matter more in the coming months. If you are a founder, it may help to think of what changes can be done to existing product-lines to either reduce cost to customer or improve their returns. Those are the only two things that will matter when speculation around products go flat.

I reached out to Ivangbi to get his thoughts on why utilisation rates have remained flat and for added context on Gearbox. He was kind enough to send me a well thought out audio-explainer on the mechanics at play. You can hear it below.

The capital efficiency component becomes even more relevant when it comes to consumer-facing apps. Because you are competing against the unit economics of traditional banks and fintech firms. Unless there is an incremental decline in cost, users may not make the switch.

We have seen this play out with on-ramps. Ventures like Moonpay and On-meta have drastically reduced retail users’ time and capital costs in buying small amounts of crypto. It used to take a few hours and at least $20-$30 to purchase small sums of crypto. I tried On-meta the other day, and they had collapsed the cost down to $4 and a few minutes.

The gambling that got us here, won’t make us relevant for the next billion. Which leads me to my next lever for unbundling – identifying the next billion.

Context Building

We often discuss the billions of dollars in dry venture capital funding waiting to deploy. And it is no longer rare for startups to raise tens of millions of dollars. But even with all that capital, founders rarely have insights into who their target customers are. The most sought after data-set by early-stage founders today is the cost of acquiring customers (CAC). Very few people know what it costs to acquire a transacting user in the industry. Even fewer understand the historical pricing for it.

Historically, it was acceptable not to have this data. Because token incentives often meant founders did not have to go through paid channels (like advertisements) to onboard a user. The protocol bore the CAC. But how do you hack through this if there are no plans for a token in your immediate roadmap? This is the struggle most ventures that are rich in (equity) funding have to battle.

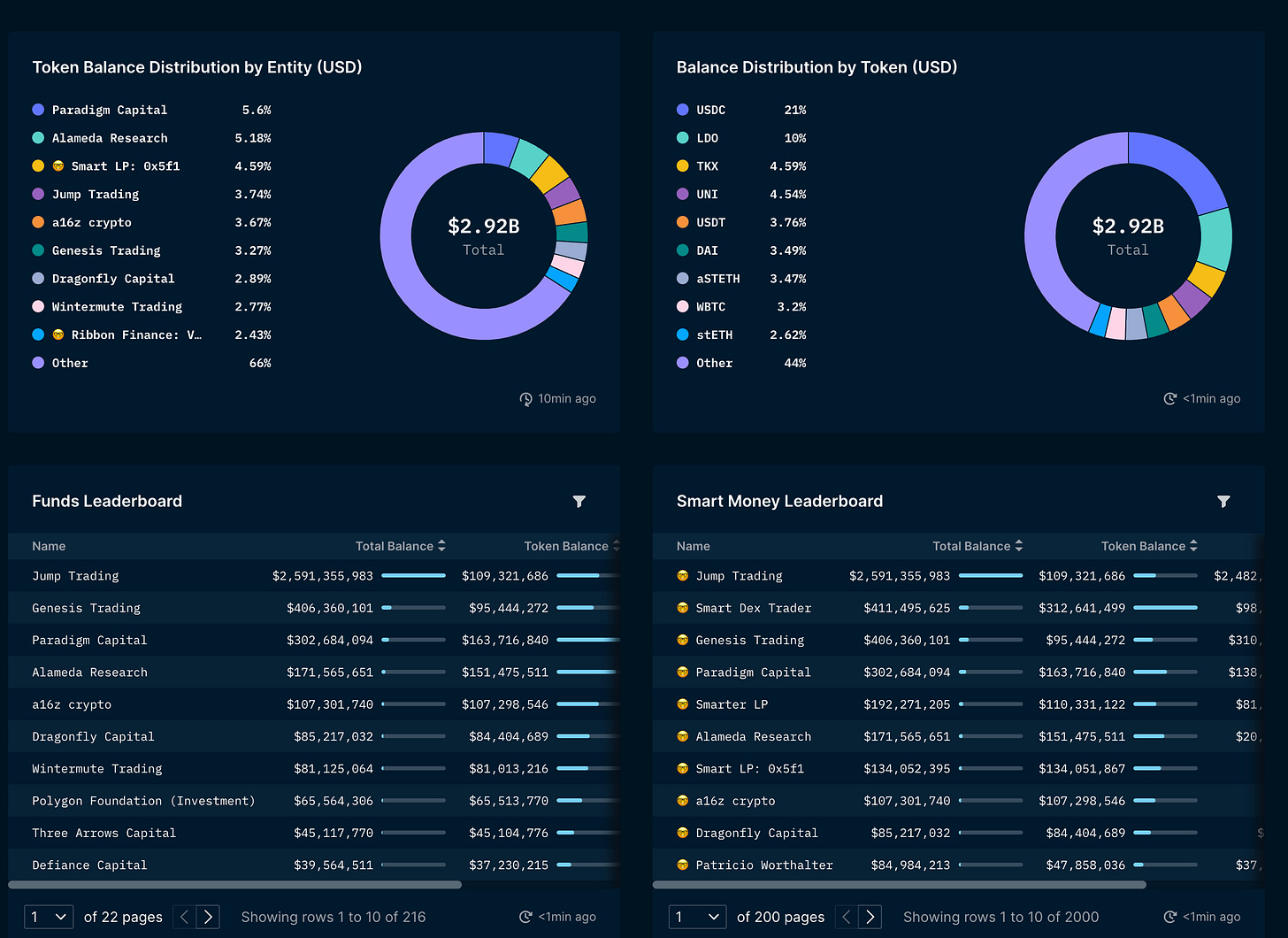

Assuming you do have the CAC data, there needs to be more understanding about the user personas. Earlier, you could operate with the knowledge that someone using Uniswap is just another degenerate yield farmer. But as the industry grows, the kind of users these products have will evolve in very complex forms, and there need to be tools to identify them.

For instance, the general assumption is that the average mobile-based gamer is a 12-year-old trying to keep himself distracted at the family dinner. On the contrary, many of the mobile gaming industry’s paying users are 40-year-old women taking a break.

Nansen recognises this need. That is why their product hinges on tagging user personas based on the actions done from a wallet. For example, tagging wallets as “smart money” or “Heavy Dex Trader” enables on-chain sleuths to get context on who is behind a particular transaction. A handful of new ventures are in the “contextualising” user persona business. Layer3, Galxe and Rabbithole curate users that new startups can target through quests.

Newly launching startups often collaborate with these platforms to identify and target their initial users. Platforms like Layer3 do not use historical data to identify users as Nansen does, but rank users based on the actions done within their platform. For example, say you have a user that has done every gaming-related activity on the platform; it may make sense to target that specific user for a new game’s UX as it comes to market. A user building an on-chain identity on the platform benefits exponentially with each recent activity, as only a handful of users would have done them all.

It may serve well to look at niche verticals if you use context building as the lever to unbundle. For instance, as the NFT boom occurred, a new class of portfolio management and NFT discovery platforms launched. More recently, gaming as a sector has been pursued by the likes of Fractal. The reason why this occurs is that each new vertical has entirely different consumer personas.

For example, a user interested in gaming may not care about a complex new DeFi yield farm on Arbitrum. But they may stay up late to see their favourite twitch streamer try a new Web3 game for the first time. And if you are a founder coming from the gaming vertical, it may be easier to collaborate with a known twitch streamer, than to get a “crypto-influencer” to tweet about you.

Ease of Use & Discovery

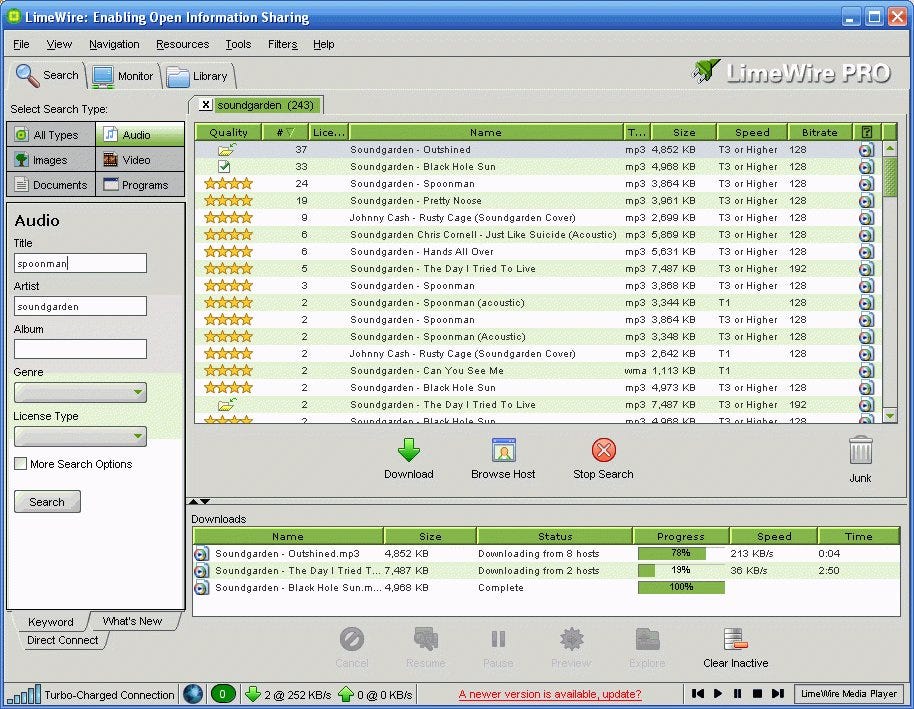

Consumers struggle to find the right tools, much like start-ups find it difficult to identify the correct user. One way to think of it is that we are in the LimeWire era of dApps. Users come for the yield and become stuck due to the hacks. The lack of entry barriers to shipping products is what makes Web3 interesting. But it also exposes users to ventures that are not production ready.

One way to mitigate this situation is through curation. For example, Darren Lau’s Daily Ape quickly became a town square with some 55,000 people sourcing their news. Similarly, Sov’s Compendium curates tools for users interested in analytics and newsletters. Both of these are user-generated curation engines that funnel people to good resources.

But there is a different approach to things and that is through data platforms. At scale, it looks like DApp Radar or Token Terminal. Both use on-chain data to shed light on the number of users and their activity on the prominent DApps in the ecosystem. Likewise, DeepDAO sheds light on the activity that occurs at DAOs.

Notice how each of these has gone into specific verticals? One pursued DAOs, while the other shares DApp’s figures and a third made it easier to look at blockchain applications through the lens of traditional financial metrics. They are all data platforms, but they repackage data to be helpful for a different subset of users. Over the next few years, multiple curation engines that show the same data packaged in other formats will become the norm.

Why? Because you can only go so far with knowing the frequency of a transaction or volume of NFTs traded. You need industry-specific context, which only comes from individuals who have already worked in the industry. Users of these products will need comparables with traditional alternatives to notice if a Web3 product is better. One example of this is RWA.xyz. It shows how real-world-asset lending platforms in DeFi compare against one another.

As the industry is in a trust deficit era, we will need products that give deeper insights into platform usage in vertical niches. The only way to build legitimacy is through radical transparency. But not everyone needs data to make a choice. The end user often wants a “walled garden” where they have what they need.

This is where founders building SDKs for embedding features like bridging, lending or trading come of relevance. They take on a single component (like swapping assets), unbundle it and offer it as a feature to multiple businesses like MetaMask.

Founders pursuing the unbundling strategy benefit from the volume that comes with the massive distribution tools like MetaMask already have. Users on the other hand, benefit from not losing all their money interacting with an unknown smart contract. Biconomys Gasless SDK for instance, quite recently enabled over 600,000 first time minters of the 100 thieves NFT to get their first NFTs without spending any gas.

Building Moats

Let’s recap what I just said. Markets swing between bundling and unbundling due to the latent lack of liquidity of capital and attention in an emergent industry. During periods of peak liquidity, it is possible to bootstrap an aggregator and find traction. But when nobody cares, it is best to look at smaller subsections of users that need you due to a lack of alternatives. These users are stickier, spend more and provide valuable feedback that helps expand the product.

Unbundling, at its core, is about throwing out the fluff from products and going vertical on a niche. It gives firms a competitive edge against their incumbents as it changes the unit economics of servicing customers. When a venture struggles with distribution, extracting more dollars per user makes the difference between shutting down and raising a follow-on round. Vertical specialisation enables founders to charge more due to a lack of choices faced by consumers.

A key reason why we will see more firms unbundle in the coming months is moats. At an age when the industry is flush with capital and devoid of users, firms will seek to find mechanisms to defend themselves. Unbundling enables just that.

New entrants cannot replicate the proprietary models built to identify users (at say, Nansen) or the returning users on a platform like Layer3 overnight. The business relationships SDK providers built over the years are hard to compete against. So in essence, unbundling makes early stage ventures harder to compete with.

Everything I said assumes we will be battling a lack of speculatory appetite and a trust deficit in the tools we build. A bear market is not really about numbers going down alone. We die out of irrelevance before insolvency kicks in. Unbundling is about making tools relevant enough for users in a vertical to keep returning to what you are building. And differentiating ventures enough to avoid battling for the same set of limited eyeballs.

I will see you guys next week.

Joel John

This article has been written and prepared by the Joel, in collaboration of Global Coin Research a group of dedicated professionals with extensive knowledge and expertise in their field. Committed to staying current with industry developments and providing accurate and valuable information, GlobalCoinResearch.com is a trusted source for insightful news, research and analysis.

Disclaimer: Investing carries with it inherent risks, including but not limited to technical, operational and human errors, as well as platform failures. The content provided is purely for educational purposes and should not be considered as financial advice. The authors of this content are not professional or licensed financial advisors and the views expressed are their own and do not represent the opinions of any organization they may be affiliated with.

*****