Has Crypto Failed?

This article was originally published at https://www.decentralised.xn--co-02t/

Blockchain natives have gone from arguing about how Ethereum may be better than Bitcoin to seeing ~180+ chains active in five years. The multi-chain world is not coming. It is here today. Today’s sponsor is a leading player empowering protocols to move data and assets between chains. Building the nuts and bolts we need for interoperability to scale.

Socket has enabled billions of dollars in transactions over the past year for their growing ecosystem of 50+ applications. They are now set to revolutionize cross-chain composability with their new development. Stay updated on what they are up to by following their Twitter here.

GM!

I’ll get straight to it. It’s been a rough few months. When turning up to work, every morning felt like a battle. Working in the financial sector in the past quarter may have made many of us recognise why our ancestors preferred “stable jobs” with meagre pay at a government office. One of the largest exchanges has collapsed, token prices are down 90% from their all-time highs, and the average dApp today likely sees less than 100 daily average users. It would make anyone wonder …

Has crypto failed?

I spent the past few weeks trying to understand where we are with crypto as an asset class, how it relates to emerging technology cycles from the past and what’s next for us. A good friend and overall badass, Roby John, suggested I read Technological Revolutions and Financial Capital by Carlota Perez for some answers. So today’s piece summarises my thoughts and observations from the past six weeks. I will send a summary of the book’s notes later. But, for now, I will try to contextualise what has happened in crypto using the information we can glean from similar bubbles in the past.

Understanding Bubbles

To define a bubble, we need to study the incentives behind pricing. We buy goods like coffee or bread because they fuel our day-to-day activities. We need them. Discounting inflation, their prices more or less stay the same as the supply and demand mechanics behind them are defined. Even if a commodity like coffee surges, consumers would have cheaper variants they can turn to.

There is a complex machinery behind agricultural commodities’ production, storage, transport and pricing because everyone needs food. So unless it is a luxury consumption item – like Wagyu beef, we see predictable pricing. When we don’t, there is a public outcry, and governments rush to get prices back to normal because nobody wants angry mobs with torches and pitchforks as they were in France in the 1780s.

Take a more complex instrument like equities. The pricing is more or less centred around what it allows you to access. In more conservative societies, people acquire stock, assuming that well-run business machinery can provide dividends. During periods of loose monetary policy and low-interest rates, speculators tend to take loans thinking that the interest rate will be lower than the appreciation of the stock’s price over time.

It is easy to predict pricing models here because we have a hundred years of data. For instance, we have two centuries of data on income generated by energy companies. It is easy to model future price performance for those assets based on past records. The same can be said for revenue multiples used for internet companies that came around in the early 2000s.

The pricing of assets that have been around for a while is within reasonable bounds because we have historical precedents for what they trade at. It gives them a sense of predictability. Now we come to something like governance tokens for platforms. Or: monkey pictures on a blockchain. Suddenly, the predictability of an asset’s price is replaced with assumptions.

One establishes a market restricted only by human imagination and greed, which exist in abundance whenever profit motives come into play. Looked at through this lens, bubbles are a period of mispriced assets – usually designed to be artificially scarce, pursued by many buyers with the intent of selling for a profit in a short period.

Every bubble throughout history has a repeated few characteristics. History doesn’t repeat. But it rhymes. Like Eminem does with his lyrics – or something like that.

1. A new asset type or technology

Every new technology has a bubble linked to it. Except, perhaps, the wheel or fire. One of the earliest bubbles took off in the 1700s, with equity as the new instrument being traded. The Mississippi Company, for instance, aimed to generate cash flows from exploiting resources in South America. John Law spearheaded it. A colourful character who, among many things, was an alleged murderer and the founder of paper money. There were similar economic bubbles for the Railways, bicycles and even telephones.

Early on, the human imagination tends to expect too much from nascent technology. It takes a few decades before the technology catches up to expectations. Think of the late 1990s. Many firms that went bust during the dot-com bubble were solving relevant problems as long as the number of people on the internet grew. But back then, the internet was a luxury a small portion of the world could afford. As of 2020, some 50% of the world is online. This supply expansion (on the consumer side) meant sufficient liquidity (of attention and capital spending) for very niche ventures–even for something as niche as selling foot pictures online.

2. A lack of data

When a new technology comes to market, more data is needed to show people that their actions are stupid. People don’t buy energy stocks at a 100x price-to-earnings ratio. Because decades of data tell them it’s a bad idea. New technologies don’t carry the same track record. In this context, risk-taking behaviour seems prudent, especially for someone seeking to escape poverty. Consider the example of bicycles.

In the 1890s, when bicycles took off, the assumption was that 750,000 cycles being manufactured for a population of 35 million (in the UK) would translate to cycle manufacturing firms being in massive profits. The reality was that, within a decade, American manufactured cycles flooded the market in the UK, and local, listed cycle manufacturers went bust. Some 40 listed cycle companies went bust in that cycle.

Crypto has a similar tendency. While tools like Nansen and TokenTerminal increasingly make it easier to verify and assess “real” economic activity on the networks we deploy money into, data literacy has not risen in proportion. And it takes a while before the market picks up on the skills to do that.

3. Inflated Expectations

New technologies capture the public psyche because they offer new ways of doing things. The telephone allowed you to yell at someone hundreds of miles away. The railways allowed agricultural produce to be transported and sold in different states. Figuring out how to refrigerate said produce enabled people to freeze the food so they could relish it in winter. New tools spur human imagination. This makes market participants take on more risk as our assessments of the situation are no longer grounded on reality or past trends.

Bubbles in the post-pandemic era are further enforced by recurring streams of news that reinforce what people are missing out on. In the past, people realised they missed out on an investment only when they went to social gatherings. Or when they saw a peer doing well off from a speculative bet. Today, that news is packaged, repurposed and constantly streamed to our feeds relentlessly by advisors and influencers whose primary motive is to retain your attention for the longest period. Effortless money-making never looked so accessible in the past.

A variation of this can be seen in how influencers are selling ChatGPT today. Indeed, it is groundbreaking technology. And it will tremendously impact our professional lives over the coming decade. But are the possibilities they enable being oversold? Quite possibly.

4. The arrival of a new network.

If you study the history of networks, practically all of them enabled a new bubble. The discovery of new trade routes was behind the Mississippi and South Sea bubbles. Some 87% of Western Union’s revenue in 1887 came from speculators looking for faster access to market-linked data. The Telegraph was at the crux of the bubble of 1929. The technology enabled the transmission of ticker data across long distances. Suddenly, people were no longer trading only on Wall Street. They could trade from a tiny suburb hundreds of miles away. It set the stage for what eventually became the great depression.

Black Monday in 1987? The Dow Jones Industrial Average (DJIA) lost 22% in a single day. It occurred right when programmatic selling through computers took off. The thing is, networks propagate narratives. And narratives (or stories) drive human actions

The internet strengthens narratives by spreading them globally. It also enables access to the networks that create them. Suddenly, news about Gamestop is not an American equities market matter. It is a global headline. An army of VC-backed fintech startups is open to serving someone from India (like me) or Taiwan who wishes to have exposure to these equity instruments because they read about it on Reddit. News about Beeple selling his NFT for $69 million sparked the “digital art” boom. These are outlier events whose details are propagated through networks.

Combine low attention spans, strong narrative velocities and a risk appetite fuelled by rising inequality amidst a constant feed of “aspirational lifestyles” on social media – and you have what played out in the last two years. An entire generation buying and selling junk based on recommendations from 30-second clips and funny images.

Understanding Pandemic Markets

History shows us bubbles aren’t an anomaly. Still, no past bubble in recent memory has reached the scale of digital assets in the past few months. What made this cycle so unique?”. We won’t examine how central bank policies have created market bubbles or how expanding monetary supply has contributed to one of the largest bubbles of all time. We will instead focus on the psychological reasoning behind market participants acting out the way they did.

Indeed, the past is littered with stories of bubbles. But none of them reached the scale digital assets reached in the past few months. We have not seen JP Morgan buying land in the metaverse in past tech cycles. So what makes this cycle unique? Was it Snoop Dogg’s concerts in the metaverse, or was it Elon Musk shilling dogecoin? There’s more to it than celebrity endorsements of digital assets.

The younger population today lives in unique times. We live in a period of tremendous wealth inequality. By some estimates, boomers and the silent generation are worth five times as much as the average millennial in the United States. Consider student debt; you have a population lost even before it entered the arena. One can argue that inequality has always been a part of human society and that younger generations don’t have it any worse than those who came before them.

But the boomers and the ones before them were only keeping up with the Joneses. Millennials today stress out about the Kadarshians making billions – continents away. (Yes, not everyone follows the Kardashians, but every average tech-bro, econ-nerd, finance bro or whatever variant you pick, has their version of a 20-something that’s made it big.)

Early in our evolutionary cycle, it made sense to do exactly what the guy next to us was doing because figuring out everything from scratch took resources. Exploring and researching new ways to do things was a privilege when you stood the risk of being killed by a leopard or a barbarian invading your village.

We operate with the same psychological wiring all these millenniums later. To imitate is efficient. Young people, with little to lose and an increasing appetite for risk, often imitate their peers. These individuals feed bubbles as they have yet to experience massive downturns. There is a historical precedent for this.

The South Sea bubble of the 1700s was one of the largest bubbles of its time. Isaac Newton could come up with calculus, but even all his genius could not protect him from losing large sums of money in that frenzy. Part of why people rushed to invest back then was that the average life expectancy was around 35 years.

If you were in your mid-20s, it made sense to take an outsized risk with the hopes of having a fortune in the last few years of your life. Consider that the markets rallied in the 1920s (right after the Spanish Flu) and in the 2020s (right when Covid took off), and you realise why our markets have been the way they were in the last two years. Pandemics and general proximity to death likely make us take on more risk than we otherwise would.

We need to recognise the world we found ourselves in the last few years. Stories of 12-year-olds making millions selling jpegs influenced our behaviour. The pandemic had us locked inside our houses, looking for sources of entertainment. Markets solved multiple pain points. It gave people a sense of community, a meaningful distraction and the mirage of an opportunity to generate wealth during massive lay-offs. When investing becomes entertainment, your portfolio can often become a joke. And that is where we ended up.

Combine an age of stagnant wages, ever-increasing aspirations, our memetic desires and a skewed sense of risk, and you get what occurred in the last few years. The rise in content consumption from finance influencers, folks building their entire personality around assets they have invested in and corporate CEOs taking on debt to invest in Bitcoin is symbolic of our times.

In his introduction to Capitalism in the 21st Century, Thomas Piketty summarises this age in simple terms: A period where the return on capital far supersedes the value of what it can produce.

When speculation yields better returns than creation, we rank the gamblers above the ones with the ability to produce. (He did not say that. I did)

Institutional Aping

Of course, my friends buying literal shitcoins at the toilet every morning aren’t the only reason digital assets grew into a multi-trillion-dollar industry. Institutions – or, as I’ve come to see them, leveraged degenerates with suits on – have a role to play in the equation. Let’s take venture capital as a benchmark. In the United States today, it takes a company an average of seven years to reach liquidity – from seed funding to an exit on a listed firm. During the dot com bubble, it took as little as three years.

The arrival of mega-funds, like those run by Softbank or Tiger Global, changed the trajectory of venture capital as an asset class. Firms were “repriced” into growth-stage firms at much shorter time durations. So long as they could show some traction. VCs backing startups that burn money is nothing new in the world of venture. But the velocity at which it occurred was much higher in the last two years.

When every firm you invest in can have an up-round in six to eight months, the job becomes less about picking the winners and more about buying as many lottery tickets as possible.

Large funds, in turn, have the incentives to deploy vast sums of capital. If a fund handles a billion dollars, deploying $10 million is only 1% of the fund. When excess capital is chasing a limited number of startups, it follows that valuations go on an uptrend. For context, consider that OpenSea was valued at $13 billion last cycle in private markets. Or that MoonPay was valued at $3.4 billion.

If I am to take public market comparables from today: Coinbase is at $10 billion. And PayTM – one of India’s leading wallet providers – is at $3.8 billion. Are Coinbase and PayTM worth less than OpenSea and Moonpay? I don’t know. But there’s a mental heuristic that was likely at play. Deploying increasing sums of money at higher valuations would be fine, so long as there is a healthy public market to exit into.

Public markets are benchmarks of where private investors think a startup can eventually go. Say I see a listed firm valued at $100 and an associated player in the early stages at $1. When listed, this can be worth 100 times more. Naturally, early-stage investors only make a few investments. They spray across players – or diversify, as the cool kids call it. Assuming you make ten bets of $10 each, and one of them goes to $100 – you have broken even on all the bad bets and made a good return. (I discount fees, dilution and lawyer retainers in this hypothetical example).

But the story shifts when public market valuations converge with private market ones. Remember what I said about how data availability helps us price things early on in this piece? Any time a firm like WeWork or Beyond Meat goes to public markets, there is a precedent for what the firm should be worth. This means valuations would reset to more realistic figures once a firm lists. So capital allocators have a choice to make once a firm goes public in a declining market.

Do you still tie up your capital in an illiquid, early-stage venture or directly buy in the public markets as Softbank did in Q3 2020?

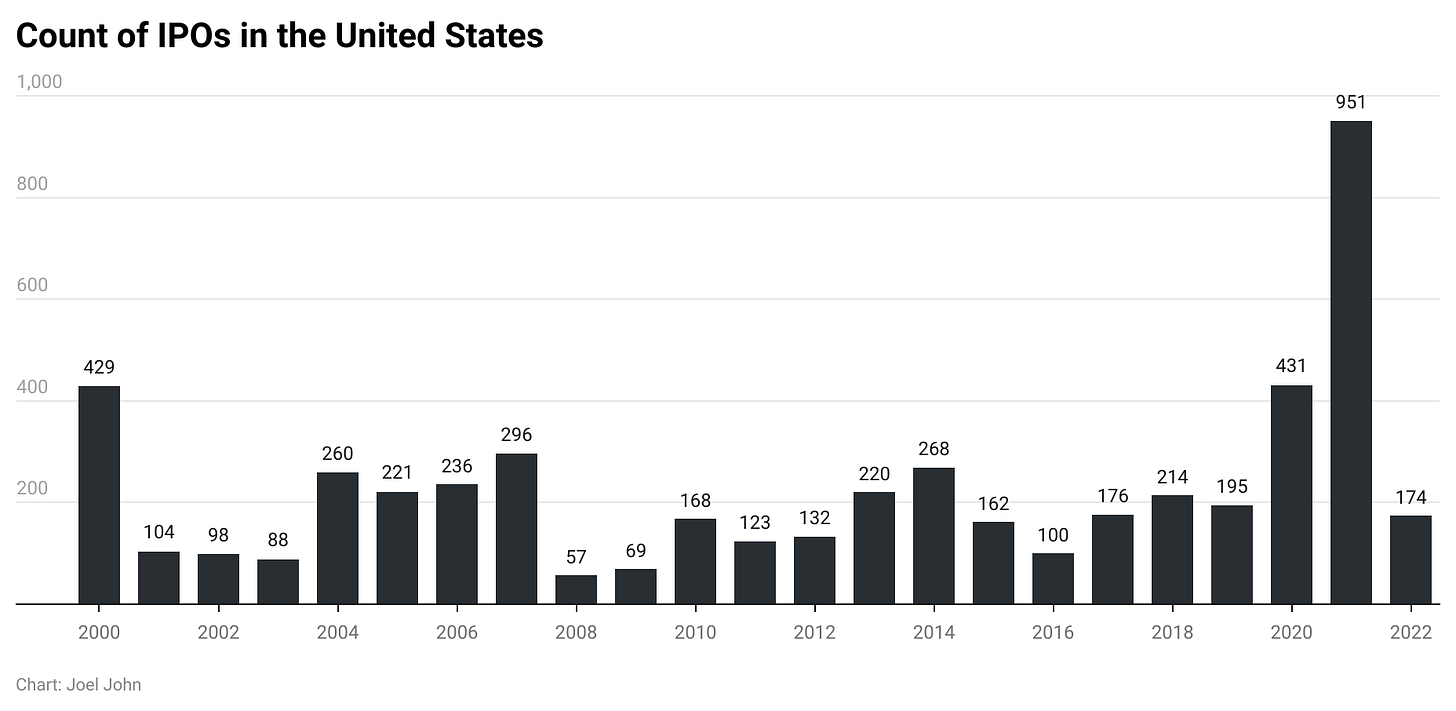

The saying goes, “money begets money”. The phrasing should be liquidity begets liquidity. When public market participants don’t see returns, private market players are sitting ducks. Because the appetite for being risk-on and deploying money to early-stage players is practically non-existent. There is a direct correlation between the number of IPOs and the amount of capital deployed in early-stage venture deals. VCs rotate money back into new startups once they see returns from a listed firm. The chart above shows why there was a rapid increase in VC activity in the past few years. The rise in number of IPOs likely contributed to it.

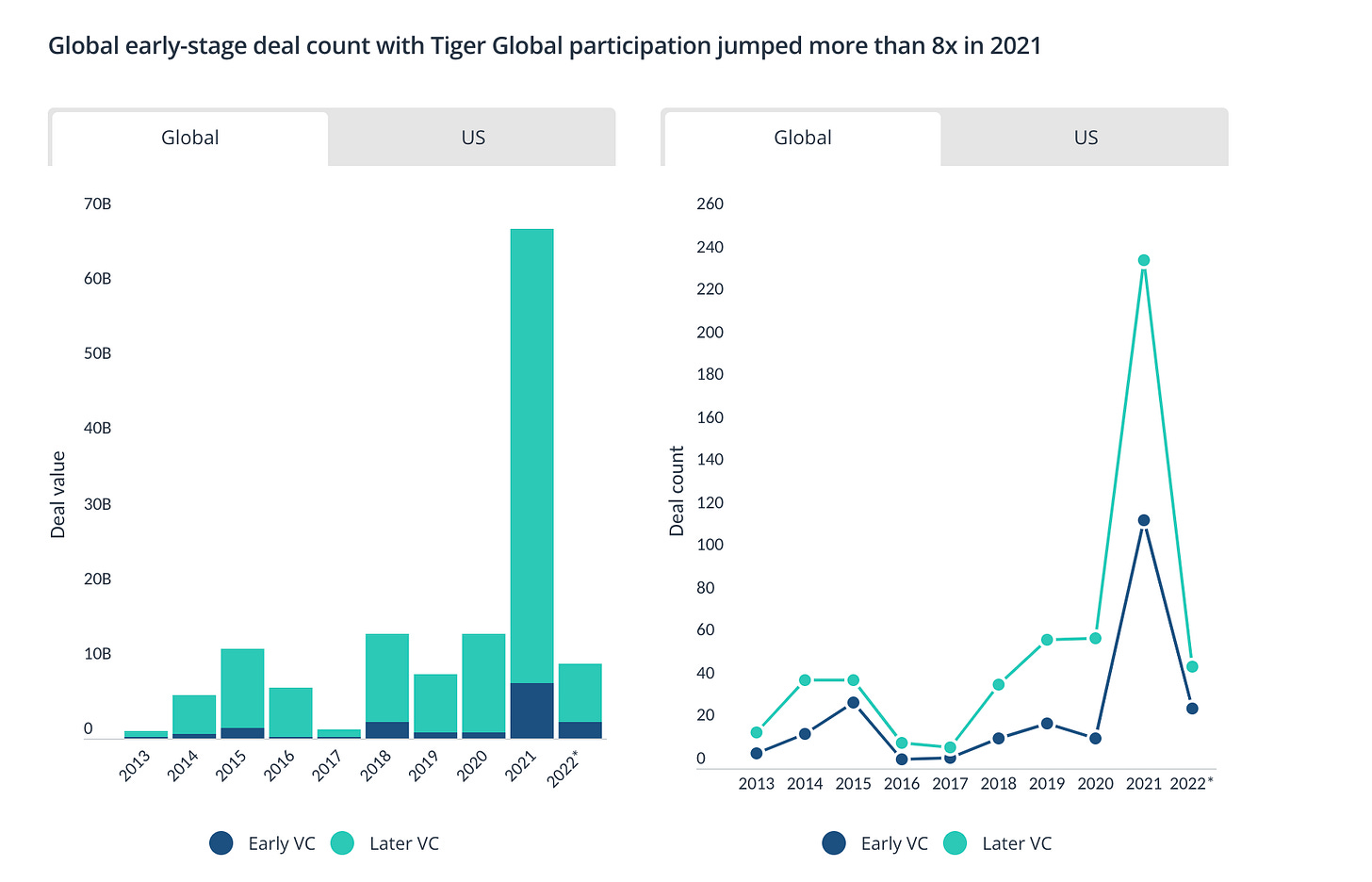

It works the other way around too. If venture capitalists don’t see any immediate avenues for liquidity – the proverbial tap with money flowing through it is switched off. For 2021 – Softbank averaged three deals every week. Not entirely an outlier, given their team size across the vision fund is ±400 people. But the stark rise in the pace at which capital was deployed becomes apparent when you consider Tiger Global’s investments over the years, as shown in this chart from Pitchbook.

For perspective, the amount of capital deployed by Tiger alone went from ~$8 billion in 2019 to ~$70 billion in 2021. You can see similar spikes in the count of deals done too. So on one end, you had an endless influx of capital supported by healthy public markets. And on the other end, you had a limited supply of startups that were venture back-able in the first place. Combine the two, and you have the startup frenzy we saw in the last two years. In other words, the party we just saw ourselves in the past few years has ended. And it may not return for a good while. Cash flow rules everything around us for the foreseeable future.

What played out between institutions and startups within the digital asset ecosystem? Much like the public markets were kind to founders looking to list their firms and seek liquidity, the digital asset space was filled with new mechanisms to provide liquidity to active participants in the market. SBF’s now hilariously terrible explanation of DeFi Yield farming in a conversation with Matt Levine from Bloomberg takes the cake for epitomising everything wrong with the last cycle.

Verifiable Madness

What made Web3 unique in its insanity is how retail interest had been piqued and the pace at which retail liquidity entered the blockchain ecosystem. Individuals no longer had to invest in a distant vision of what blockchains could enable, as was the case in 2017 with ICOs. Instead, you could invest in assets that were here and now. The “yield” from DeFi was perceived to be real.

Aspects like play-to-earn and NFTs could engage retail minds in a way concepts like peer-to-peer Uber or on-chain supply chain never could. Combine that with stimulus checks and lock-down boredom, and you have NFTs being traded for billions of dollars. Everybody wanted to be in on the next Bored Ape. Every firm wanted a slice of the play-to-earn pie.

It was quite straightforward to benefit from this as an institutional investor. You invest in infrastructure that enables founders to go to market (like Alchemy), or you invest in the outlets where users trade these assets. Looking through this lens, it’s easy to understand why so many renowned names piled onto investing in FTX — they could avoid directional risks of random altcoins while still benefiting from the frenzy itself.

Facebook or Amazon have to spend years bootstrapping network effects to get people to spend money on their platform. Facebook’s massive failure in building anything of (real) relevance in the metaverse is symbolic of how hard it is to get retail users to spend money unless the value proposition is incredible. Nobody wants to spend all their time pretending to be cartoons without legs. We do sufficient acting in our own avatars on social networks already. Contrast this to what we see in the crypto-native variation of the “metaverse.”

It was common to see land plots and NFTs sold for tens of thousands of dollars. The chart above shows that most of them tend to zero over time. For the first time in human history, we had the tools to build a bubble of bubbles. During the South Sea Bubble or the Railway Bubble, it still took years to produce any semblance of a viable business. It took vast resources to pretend a business existed beneath the frenzy. In the age of everything digital, an afternoon’s worth of coding was sufficient to get capital from investors that often knew nothing about the digital instruments they were rushing to buy.

It is unfair to suggest institutional investors were investing in creating platforms that sold useless assets to unknowing retail users. Because many of them were imitating what their peers did. Or they were responding to what their investors (the LPs) wanted. But it is within reason to think that inflated measures – for TVL locked in DeFi or NFT instruments traded – were a driving force behind the sheer amount of money that entered the ecosystem in the last two years.

This massive influx of capital has, in turn, incentivised the rapid financialisation of everything. When you obsess about the fastest way you can get a customer to transact instead of what the customer needs, you get a sea of predatory instruments with nothing worthwhile to offer. One sells risk to curious customers that seek novelty. Naturally, this leads to market abuse in a brief period where regulators have not yet caught up with what is happening in a new market.

Was it all a dream?

A few days back, while on a walk at a stretch near the beaches in Dubai, a friend told me he is “confident” in his abilities to make money regardless of where the markets go. He is a CXO at one of the large blockchain firms and, by all means, has good reasons for his confidence. People like me, who entered the market in the 2010s, have benefitted from one of the largest expansionary phrases of monetary supply. We have only ever seen good times – with temporary blips of fear. If like me, you were in your 20s, you did not have much to worry about.

My response to him was to allude to the fact that all of technology as a sector may have been in a multi-decade-long bubble cycle, and we may soon hit a moment of reality much like previously “hot” sectors did. There used to be a time when working on automobiles or electronic goods was the smart thing.

The more I study bubbles, the more I can’t help but wonder if we were all living in a dream. Is all of crypto just smoke and mirrors? Or is there real promise to what we spend so much of our time and energy on? It is nice to believe in Su Zhu’s supercycle, but it would also be terrible to wake up at 40 and realise I had just spent two decades of my life on technology that meant nothing. Life is too short to be building something nobody wants.

In that spirit, it is worth seeing objectively where the sector has been trending in actual traction over the past few years. I would have loved to larp about how Zk-snarks are ground-breaking innovations or that the 30 derivatives-linked DAOs with 50 users trying to farm them for airdrops are fixing finance. But “innovation” is not what I was looking for. I was looking for traction. Verifiable, quantified proof of people using these things. Numbers. And graphs with hockey sticks on them.

As a benchmark of growth for these sectors, I’ve looked at figures from 2020 and compared them to where things stand now. I took this approach because Q1 2020 is when most of the things I think have traction were mature enough for adoption but not necessarily in the mainstream. Taking Q4 2022 as the other end of the scale makes sense because we are six months into a bear market, and if all these metrics were just traders frantically clicking buttons, we would have seen a substantial drawdown in line with the Bitcoin price collapse.

If I consider that Bitcoin or Ethereum’s price is down ~75% from its ATH, I expect a similar drawdown on active users too. I then filtered down use cases that have been all the rage. Namely – stablecoins, applications in DeFi and NFTs.

1. Stablecoins

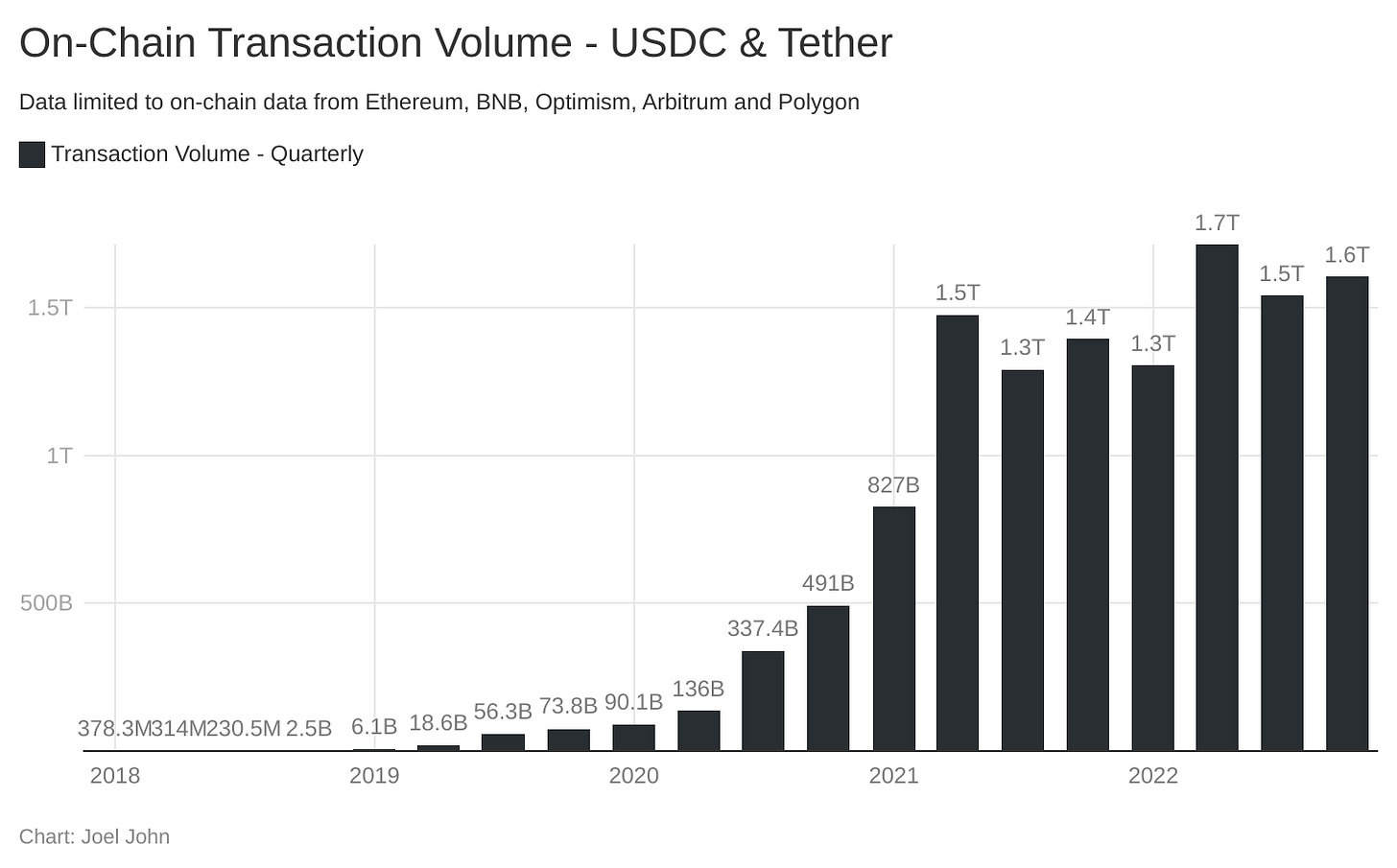

Bitcoin and Ethereum have settled trillions in volume since their inception. But they serve a niche segment comfortable with volatility in exchange for relative decentralisation of the underlying asset. The average person needs something more stable, and stablecoins likely serve their needs well. Between USDC and USDT, it is possible to have global-scale payments settled on-chain in a matter of minutes. Compare this to the transaction time necessary for international wires.

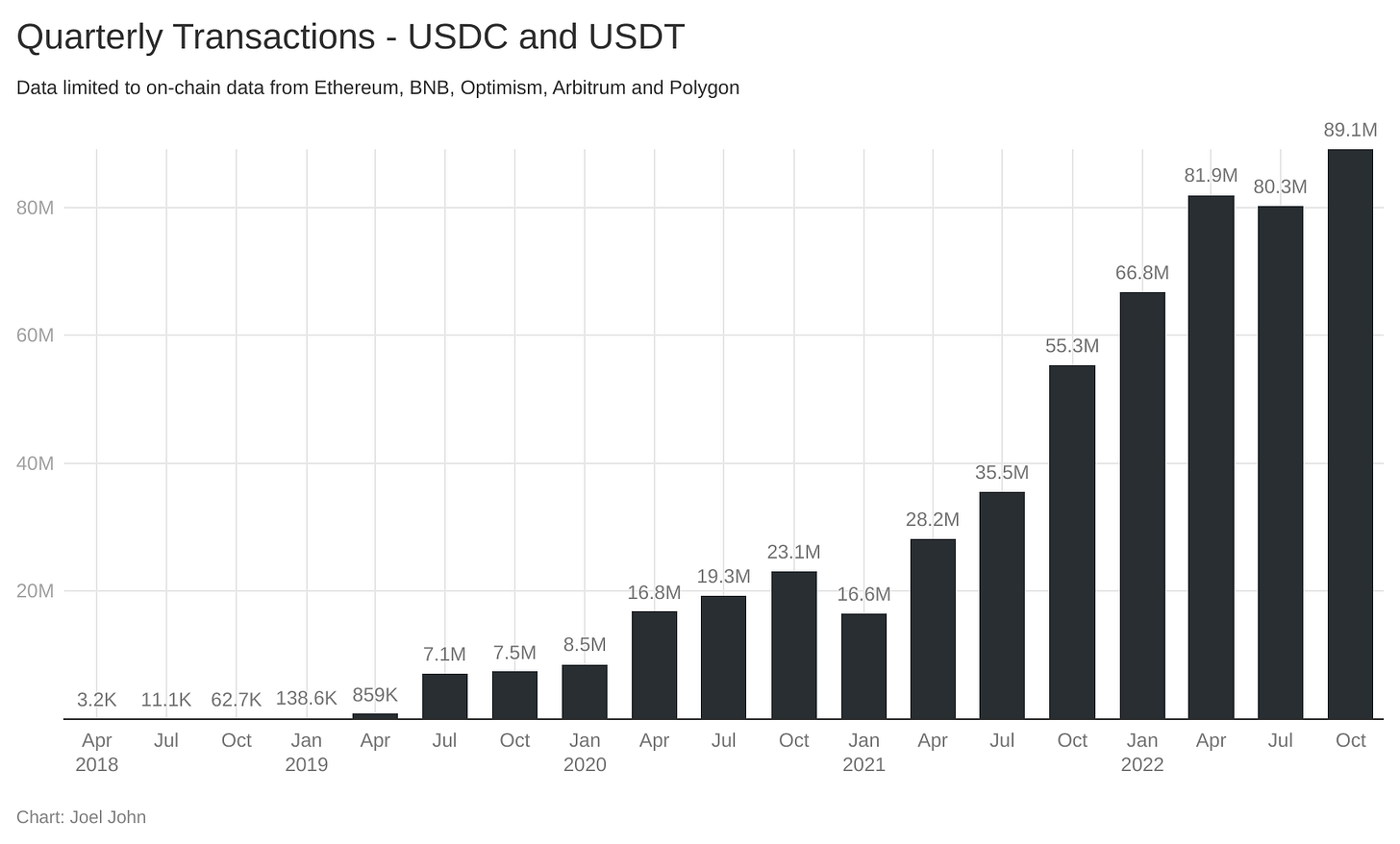

Payments settled on-chain through stablecoins have boomed to $1.6 trillion over the last quarter. This is up from ~$90 billion as late as Q1 2020 – roughly ~17-time multiple on an already significant metric. I believe the reason why DeFi never took off until primitives like stablecoins came of age is that we needed a stable store of value before complex financial derivatives could be built on top of them.

For a sense of scale, Visa processed $14 trillion in volume for 2021 across ~255 billion transactions. Stablecoins do roughly 10% of the volume and ~3.5% of the transaction frequency Visa does. This is an apples-to-oranges comparison. (I know). Visa has had a ~40-year lead and decades’ worth of network effects that come from being the preferred choice as nations worldwide have gone digital with their payments. I don’t think stablecoins – or on-chain payment settlements – will compete against them in the immediate future. Instead, I use it as a benchmark for the pace of growth.

Stablecoins will not compete against regional payment networks in most regions. No reason one should force-fit an alternative payment mechanism where alternatives already work. For instance, India’s digital payment ecosystem saw some ~72 billion transactions without blockchains or bells and whistles in the financial year 2022. Stablecoin payments, in contrast, did only 300 million transactions last year, or ~5% of what a single country manages to do.

Stablecoins will instead become predominantly practical in digital-first economies that require global-scale settlement. What does that look like?

The web, as it stands today, already has examples. Platforms like Fiverr and Freelancer bring together labour markets globally, but their payments infrastructure is a complex web that can hold onto payments for days. Artists rely on payments from entertainment utilities like Spotify and Youtube. Transfers from them can take months, if not weeks, to come through. Twitch and its adult cousin, OnlyFans, have already proved that there is a market for creators to make a living. An increasing portion of children aspires to be influencers once they grow up. Do you see a pattern? Our modes of work, learning, love, discovery and entertainment are all going digital.

Our economies have gone digital faster than the payment networks enabling them. This will matter as our modes of consumption also turn digital. For instance, in October alone, Roblox users spent ~4 billion hours playing on their apps. It may be hard to translate ~4 billion hours to years, but here’s one way to look at it.

Go back 1 billion hours in time, and you find yourself around ~110,000 BC, foraging fruits with our distant stone-age cousins. Google, Microsoft and Apple each see revenue north of $10 billion from their gaming arms. The highest number of concurrent players a single platform has seen, as per data from Githyp is at around ~3.2 million. That is the equivalent of Dubai’s population gathering on a digital platform, at the same hour, from varying points in the world.

Attention precedes capital. Up until around 2015, while people were still getting used to spending their money digitally, it was okay for payment innovations to lag behind platform developments. Back then, only some people spent most of their waking hours looking at 5-inch screens. We find ourselves at an inflexion point where money needs to evolve to enable the next step up for the internet. Slow payment infrastructures can shave percentage points off from GDP growth, as is often the case in emerging markets.

CBDCs are a response to this evolutionary arc of our financial infrastructure. They enable governments to regain control while theoretically “enabling” digital first platforms like Steam or Twitch. We will explore this theme in the coming months, but let’s get back to stablecoins.

Why did I mention how much of our time is spent in digital realms? They serve as a good context for what’s next. I could summarise it like this.

- Stablecoins have grown in both volume & transaction frequency over the pandemic years. They have been battle tested enough to suggest they can offer a parallel to traditional banking rails for creators and developers. The fact that Stripe allows creators and developers to get stablecoin payments from anywhere in the world is a proof point that validates this.

- Our economies are increasingly digital, global and, ideally, permissionless. This means the payment networks we use also need to evolve with them. For example, you cannot spend weeks between selling a digital item and the money hitting the bank. Under the regulations of the central banks they deal with, traditional banks will likely need help to move at the pace these platforms require. That is the gap stablecoins will fill.

The reason why this would be the case boils down to compliance. When a traditional bank opens up its infrastructure to unknown developers from remote parts of the world – it must engage in an ever-increasing amount of compliance. A few bad actors likely engage with the bank’s infrastructure for every few million dollars flowing through the system.

Running compliance is costly, with heavy penalties if the regulator deems it risky. So on one side, you have the rising cost of compliance; on the other, there is the loss that comes with any deemed failure to follow compliance procedures. The cost, in some nation-states, would mean a ban from operating.

Contrast this to a public blockchain like Ethereum. The “liability” for compliance is now broken between the user (when on-boarding), asset issuers (like Circle), custodians (like exchanges) and sellers (on receiving payments). None of these parties exists in some lawless dystopian society where regulations don’t matter. Each player has heightened reporting requirements as per the law.

But it is no longer contained to a single financial entity that makes a blanket statement on what is permissible and what is not. Instead, the market determines what risks it deems worthwhile or not. Some are comfortable with gaming, others with running derivatives markets, and certain others with simply providing services.

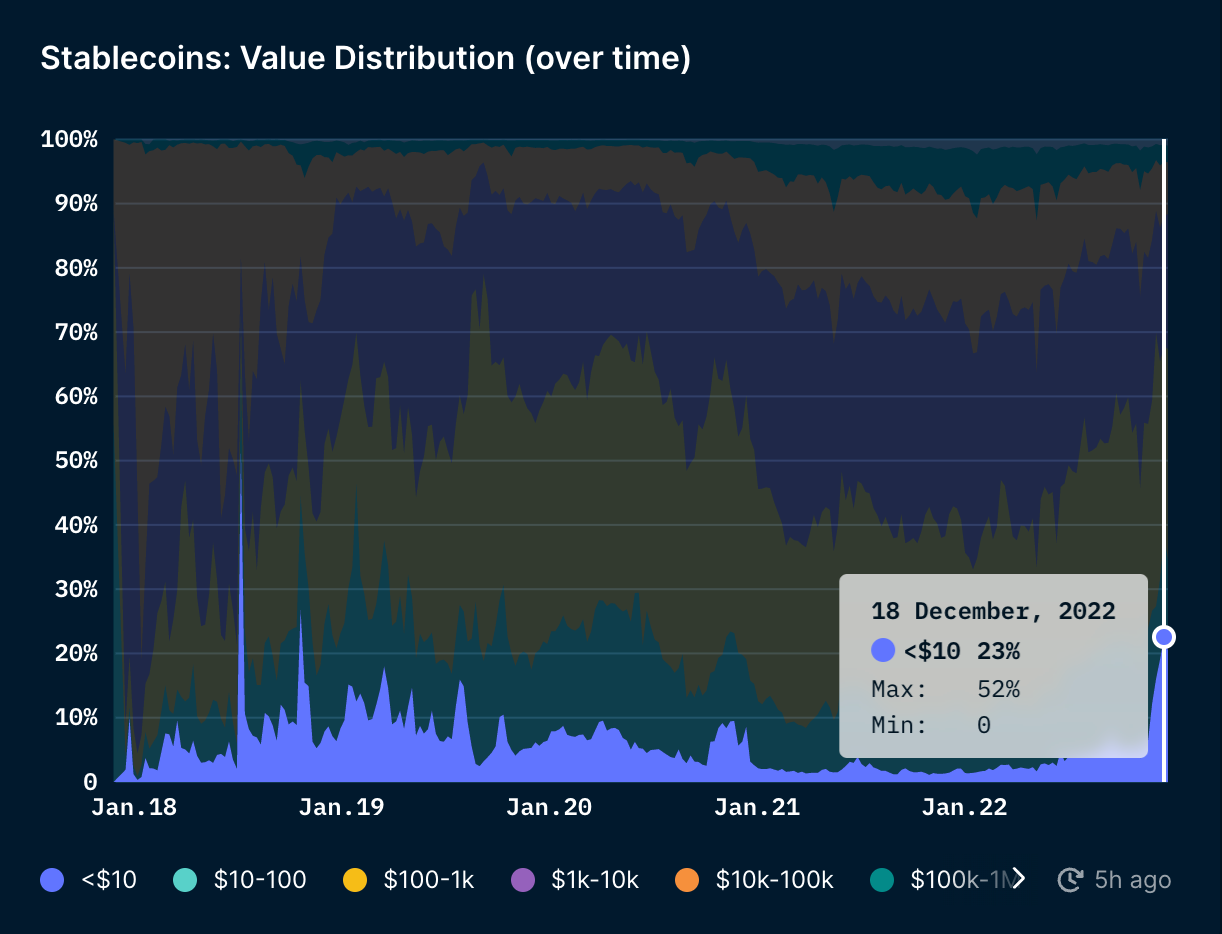

Data from Nansen breaks down transaction frequency based on amounts transferred. As of two weeks ago, transactions worth less than $10 accounted for a quarter of all stablecoin transactions. Those under $1000 were responsible for two out of three transactions. This, although ~83% of the on-chain stablecoin volume, is settled through transfers worth over $1 million.

Retail users flock to stablecoin transfers despite the high fees as they find it a reliable alternative to traditional banking rails regarding speed and transaction finality. If large traders were the only ones using stables, we’d see a larger share of transaction frequency dominated by large-volume transfers.

Will stablecoins compete with regional payment networks? Possibly not. Instead, they will supplement entirely new digital economies, specifically in use cases that require a high velocity of money. There is sufficient evidence for this already. DeFi and NFTs are two primitives that took off on the back of a two-year stablecoin supply expansion. I break down how they have grown in the next section.

Decentralised Finance

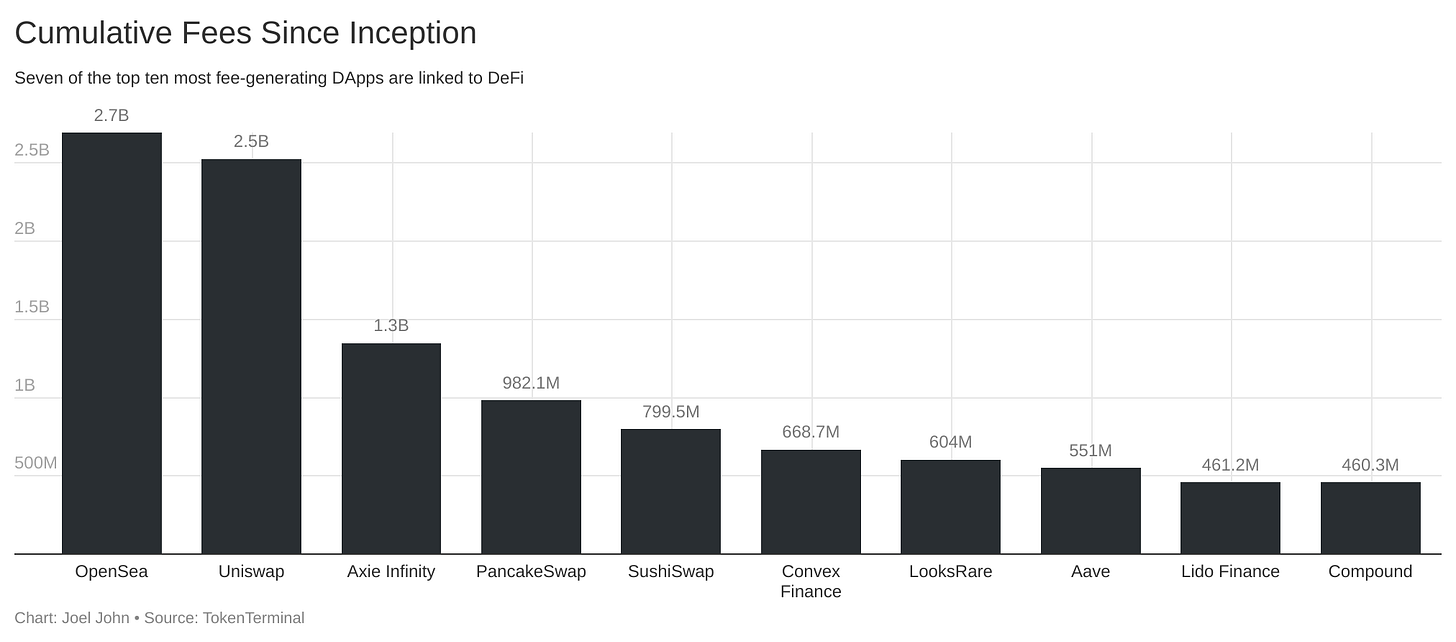

Given the fall in token prices, it’s tempting to write off Decentralised Finance altogether. There is sheer carnage. Practically, many of the sector’s assets are down north of 90%. It is a dumpster fire fuelled by terrible token economics, broken UX and esoteric instruments nobody wants. But there’s a different lens through which to look at things: fees. One way to understand how much DeFi matters to the blockchain ecosystem is by checking which applications create revenue.

I pulled up a list of the top ten decentralised applications in terms of fees for reference. About seven of the top ten belong in some form to DeFi. Selection bias? Well – go all the way to the top 25 on TokenTerminal – and you will notice ~22 of the top 25 are DeFi related. There is an argument to be made here that DeFi shows more revenue as it had a relatively early mover advantage (around 2018) compared to NFTs, which began taking off only around 2020.

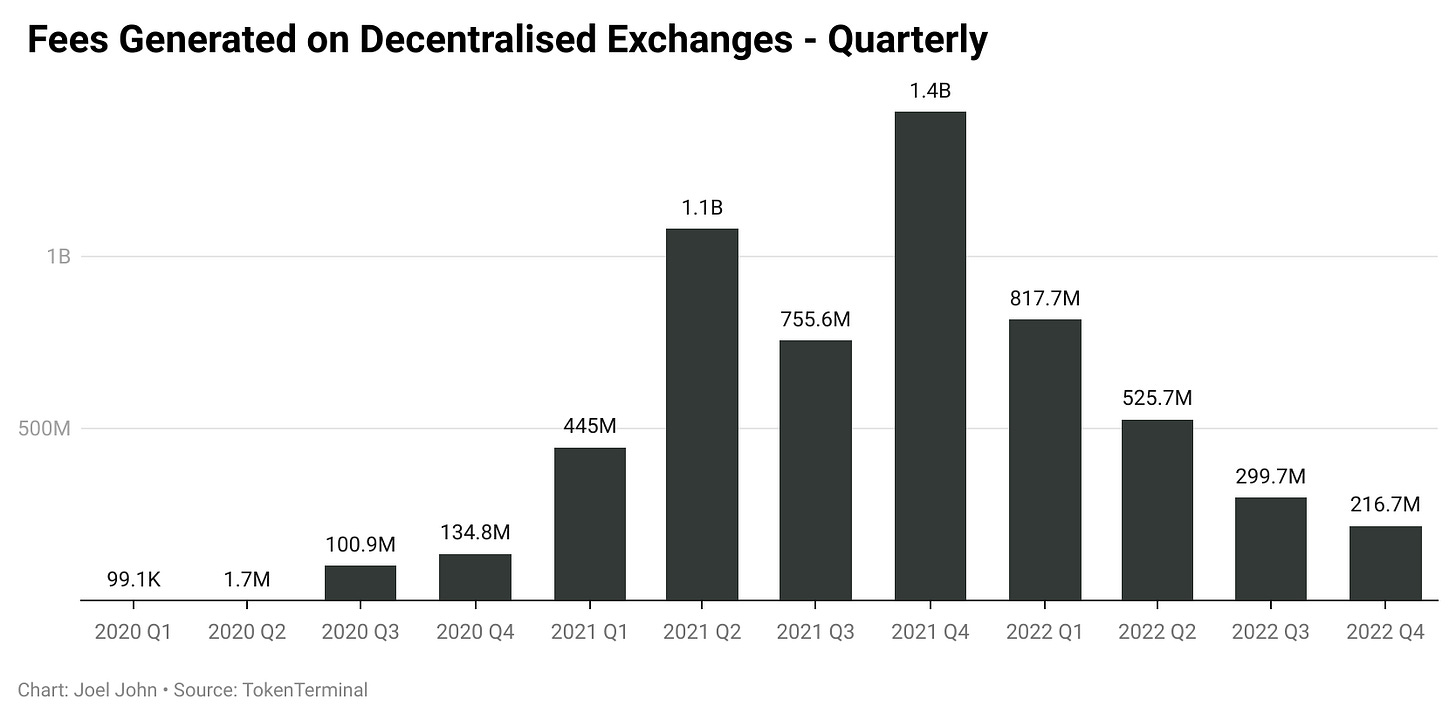

The bulk of activity in DeFi platforms comes from crypto-savvy users and applications like NFTs that are genuinely opening up the market for newer entrants. Even when accounting for both those facts, it remains that DeFi generates cold, hard cash flow in an industry that sees barely any of it. I noticed this when I broke down revenue generated on prominent decentralised exchanges.

There is the obvious observation that fees generated on decentralised exchanges are down some ~85% from their all-time highs in 2021. It is fair to say aspects like yield farming and token rewards based on transaction volume pumped this figure up throughout 2021. But to understand the whole story, it serves well to look at volume in Q2 2022 and compare it with what it was just two years back, in 2020.

I take these two vantage points because Q2 2020 was right when DeFi summer was about to take off. Q2 2022 is when Luna and 3 Arrows decided to introduce gravity to many of our portfolios.

Even if you take a conservative multiple, fees on decentralised exchange platforms grew some ~200 times between the two periods. Through the lens of the figure for the current quarter ($217 M), we are up to 130 times. In fees. Naturally, these products are predominantly used by speculators in their current form. And a prolonged bear market would displace any of their user bases. This is what I thought would be the case. Then I observed the active users these platforms have.

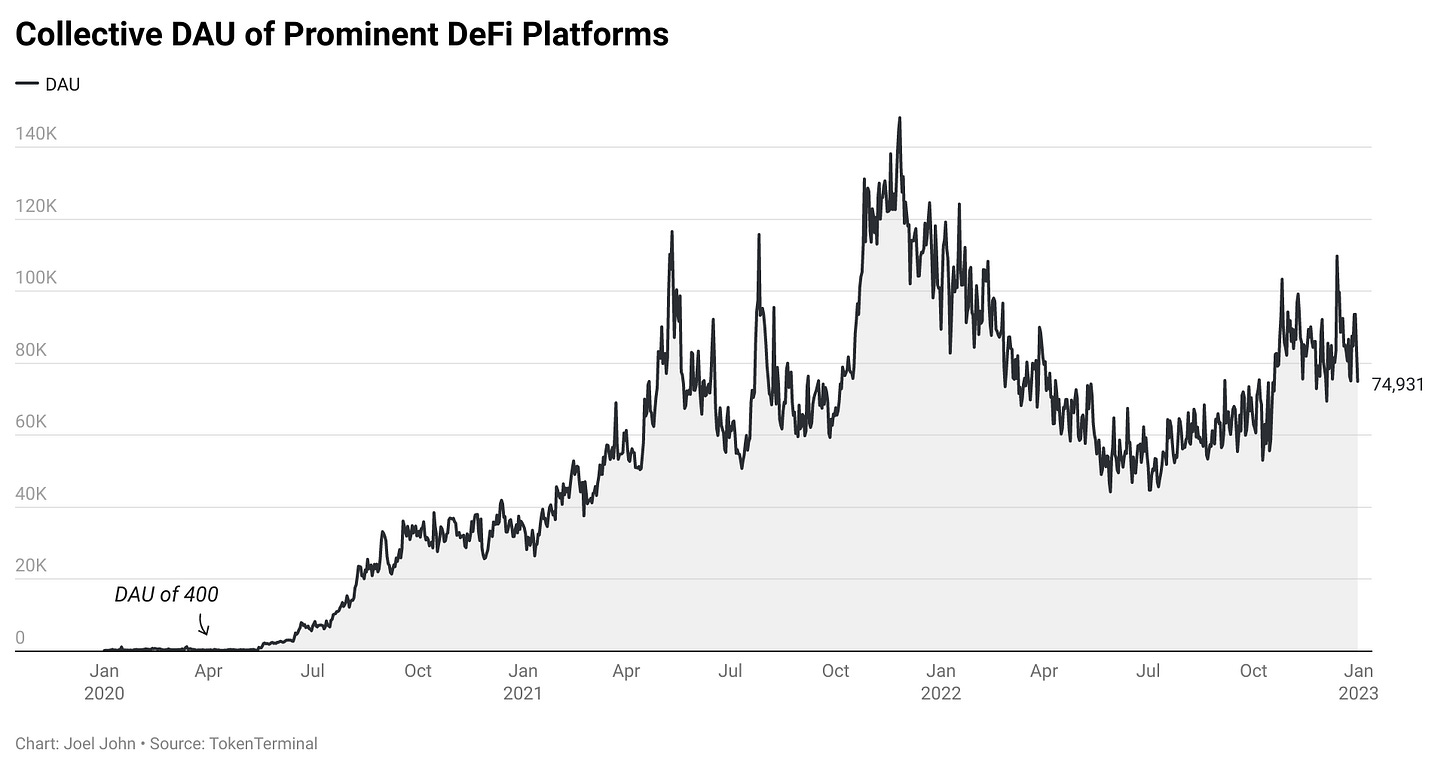

The chart above looks at the combined active users on major DeFi platforms. I presume it is restricted to ETH users. Or, in other words – people who are comfortable spending a few dollars on every trade, loan or transfer made. It was intriguing that until April 2020, there were barely ~400 people using DeFi products on a given day. That figure peaked at ~140,000 in late 2021.

Given the drastic drop-off in token prices, one could reasonably argue there will be a drop-off in users for DeFi-linked products. But the chart shows a different story. The number of active users bottomed around July this year and has been steadily recovering. At ~75,000 users, it is still up some 200 times the count of users the industry had in 2020.

Now, there are arguments to be made against this figure too. First and foremost – that Uniswap singlehandedly makes up the bulk of this DAU. Compound and Aave have had “only” a ten times growth in their DAU over the past two years compared to the multiple platforms like Uniswap do. But that is because only platforms that are engaged with active transactions daily will see daily users coming back. There is no reason for people to keep repaying their loans daily on platforms like Compound.

The figure above is on the conservative side. Data from DAppRadar indicates that cumulative DeFi user figures come closer to ~3 million on a given day in Q4 2022. This is still lower than the 9 million or so wallets that were active in the space up until January 2022. For a sense of scale, Coinbase sees around ~600,000 DAUs in the US alone. Now we don’t know if all of those users transact daily. However, the odds are high that most of them quickly glance at their portfolio. Likely at Starbucks, pretending like they have something urgent to do on their phones whilst waiting on their fancy lattes and avoiding any and all forms of human interaction. (I know, because I do it all the time).

Assuming 15% of users on Coinbase transact on a given day – it comes to ~120k users. In other words, DeFi’s transacting user base (60k-140k) comes somewhat close to being as large as the biggest listed exchange in terms of user count. As an ecosystem, the space has grown ~100x in revenue, volume and users in the two years since 2020. There is a multitude of reasons for that. As someone trying desperately to move to Singapore in 2019, I can attest that being broke helped us stay focused on building primitives that mattered.

For DeFi to be “functional” in Q2 2020, there had to be two to three years of work that went behind them in the previous bear cycle. Just years of writing code, researching and raising just enough money to keep the doors open. Those primitives grew to be “production ready” by Q1 2020. (Definitely not looking at you, Andre Cronje.)

When the perfect storm of pandemic boredom and the federal reserve letting its proverbial money printing machine loose occurred, DeFi was just in the right spot. To provide the infrastructure, a generation that just lost its job needed to speculate, invest and “yield farm” tokens globally. But if that is the only user base the industry had, then we would have seen substantial declines in DAUs. That has not occurred. This makes me believe that a large user base cares about and uses these tools daily. As prices stabilise and innovations in L2s, bridges and on-ramps improve, we will see the next generation of users come inbound.

This is not to suggest all of DeFi is a bed of roses. Our developers often forget the need for audits. You are likely better off holding your precious dollars in a bank than in 90% of DeFi primitives developed by under-resourced teams with tight deadlines and many side-hustles. I avoided mentioning real-world-asset lending or the 30 DeFi derivatives projects with the same 50 users looking to farm airdrops because these products have yet to be ready for the average user. But at a time when Sam is (allegedly) busy stealing user deposits, and the dudes at 3AC are (allegedly) giving harsh lessons on why not to lend without collateral, DeFi is proving to be the alternative that just works. Sometimes, that is all you can expect when it comes to frontier technology.

Non-Fungible Tokens

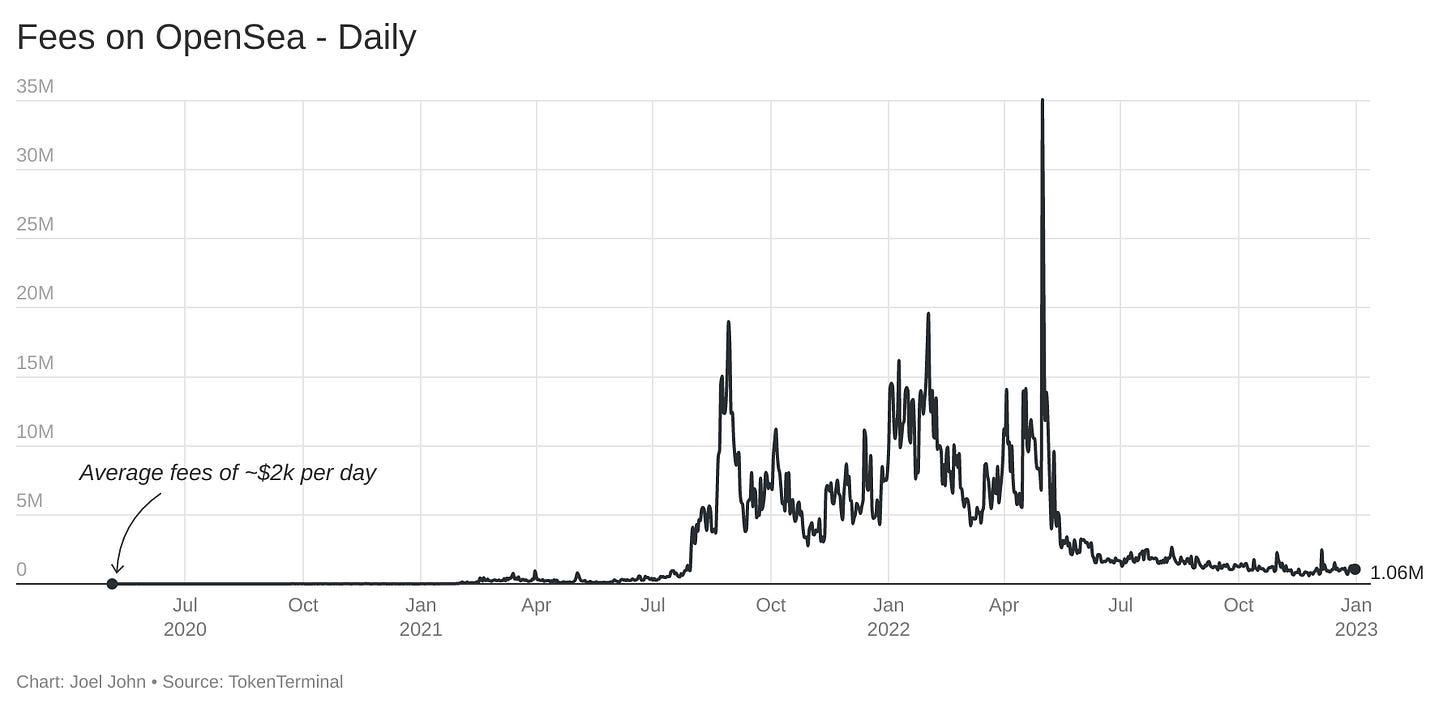

It is easy to write off NFTs as financial primitives that have failed. I mean, look at the chart linked to fees from OpenSea given above. Explaining that fees have declined from ~$30 million on any given day to $1.06 million makes a great headline. But it ignores that we are up 500 times from as late as October 2020.

There are two market forces we don’t talk about enough. Firstly, as curiosity about these digital assets declines, we will naturally see a reduction in the volume of these goods sold. People that are not speculating will not move their assets around on-chain daily. They will buy it once and call it a day. So it is only natural that volume goes for a toss.

The price decline of many NFTs further causes a decline in volume. Based on Nansen’s NFT index, a group of 20 NFTs linked to the metaverse is down ~49.5% for the year. A different index linked to 50 gaming NFTs is down ~69%. But if you take the index constituting the top 10 blue chip NFTs – it is down a mere 13% for the year in ETH terms. This is better than the S&P 500 – which is down ~20% for the year.

Is that because our pictures of rocks, monkeys and ugly pixel art are somehow of more economic value than the constituents of the S&P500? Obviously not. People have begun seeing some of these assets as stores of value they hold on to instead of being instruments of speculation. As the lending market around NFTs evolves, it is unlikely that we will see ever-increasing volume around high-priced NFTs. Instead, like in the equities markets, people will take a loan against the assets they already own.

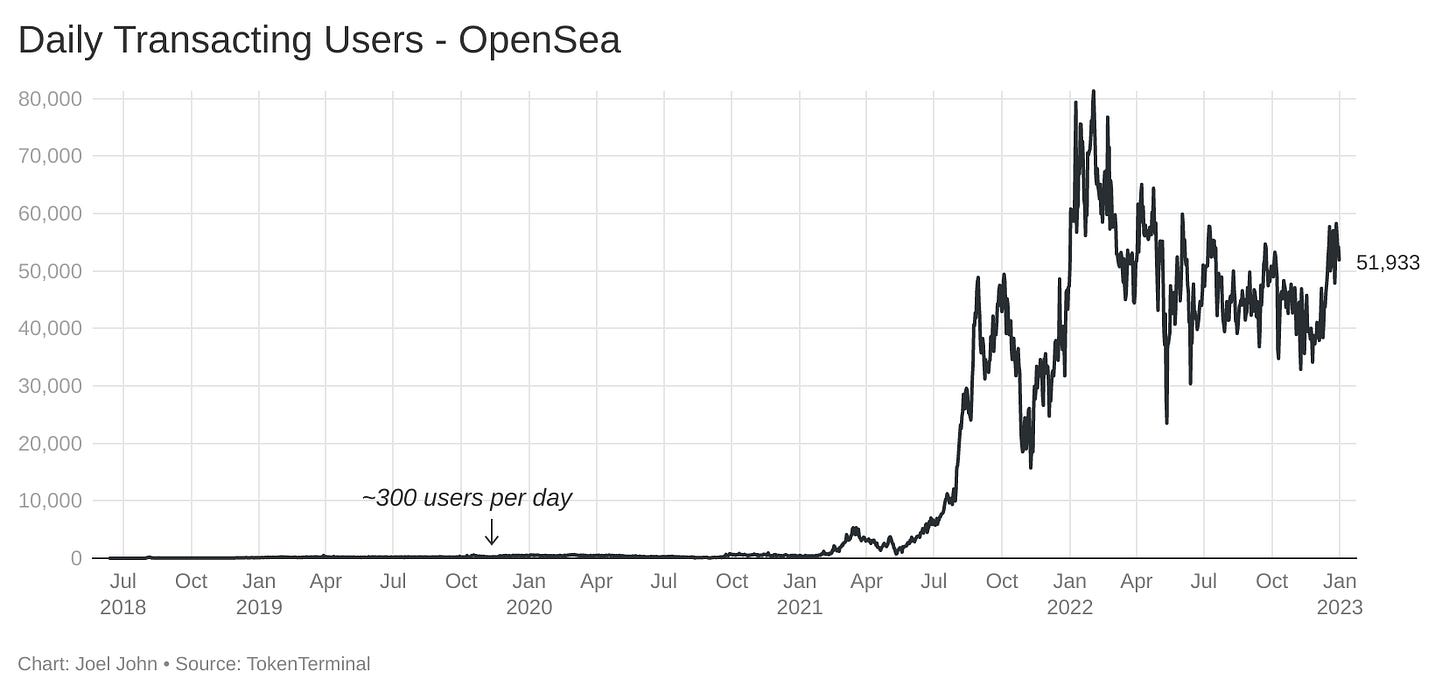

So is volume doomed to never surge back up? I don’t think so. What would bring back volume would be a mix of new applications and a return of speculatory demand. The latter depends entirely on the price of digital assets such as Bitcoin and Ethereum. Generally, only traders that sit on enormous profits go out and purchase multi-million dollar jpegs. But the former is entirely under the control of developers here and today. Despite that massive price dip, there is no decline in the number of users doing at least one on-chain transaction through OpenSea on a given day. (

According to data from TokenTerminal, the active users OpenSea has is up from a mere 300 users per day in Jan 2020 to ~51,000 as of Jan 2, 2023. According to Nansen, we see about ~200,000 users in the NFT ecosystem across exchanges every week. Has this figure seen a colossal drop over the year? Not really. The all-time high for this figure was ~430,000 users. A 50% drop off over the year in an industry that routinely attracts short-term intrigue is not a disaster, especially when that metric is up 1000 times from a mere 18 months back.

There is a different reason to be more optimistic about NFTs as a category. And that is how it is being “retail-ified.” They are being re-packaged from being instruments of speculation to ones of consumption, at price points that are affordable to the average internet user. NFTs as a technology in the last few years echoed what happened early on with mobile devices. Bottlenecks with infrastructure (eth-gas cost) and a handful of assets capturing the public psyche meant it was way out of reach for the average person.

As applications around content consumption, event ticketing and gaming took off, the average cost of an NFT declined rapidly. The chart above shows how much each buyer on the Ethereum network spent on NFTs over the last year. The spikes correlate with periods of incredible wash-trading and speculatory bets – but as you can see, they have flatlined in the previous six months.

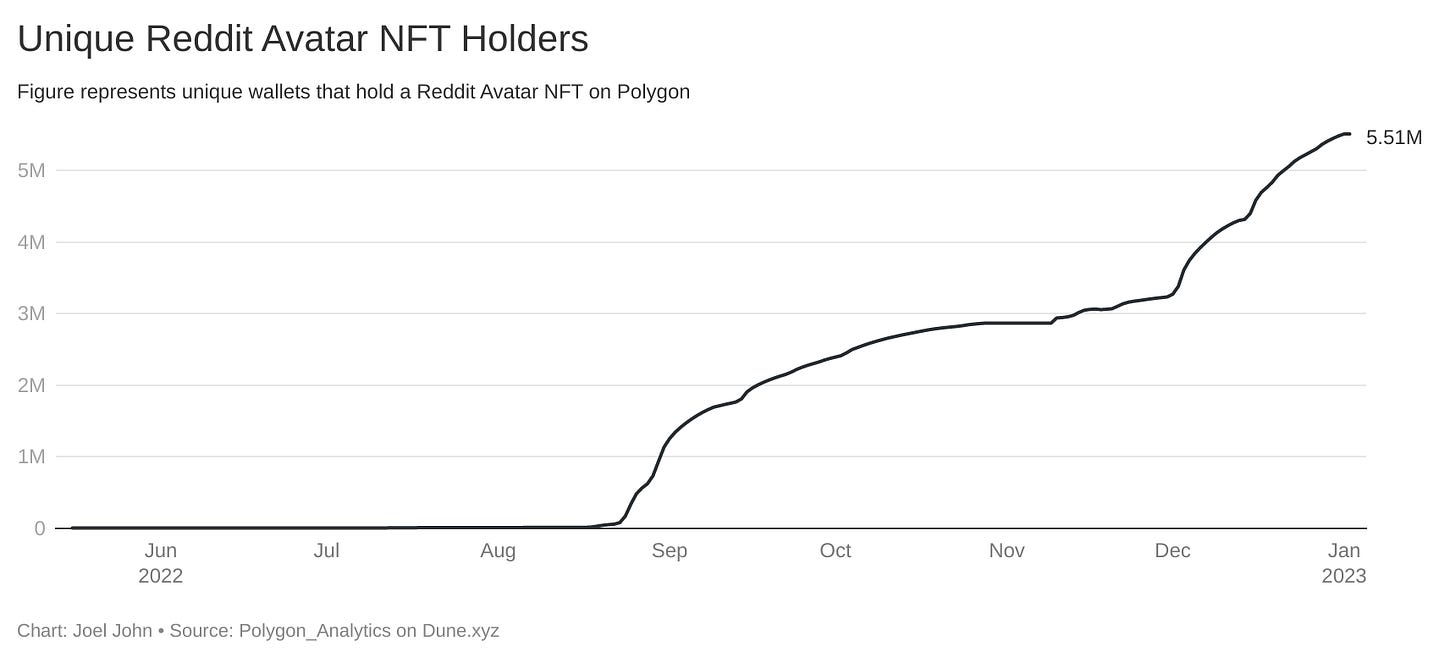

I don’t believe the average person will spend $500 on an NFT. One could argue that the asset would have failed to make any meaningful impact if that remained true. NFTs would trend towards what low-cost SaaS products cost today:$10-$50 because consumers are used to and comfortable with – spending these sums of money on the internet today. There are some early signs of the possibility of NFTs becoming low-priced, mass-consumption goods distributed digitally. And it is occurring on one of the largest social media platforms. Twitter? Nope. Instagram? No. It is happening on the weird NSFW’ish corners of Reddit.

Reddit’s Avatar NFTs were released on Polygon earlier this year. This comes after a year of the platform experimenting with tokens. As of writing this, approximately 5.5 million unique wallets are connected to Reddit. If we assume each wallet represents a user, that means close to 6% of its user base owns an NFT, But the fact remains that one of the largest NFT ecosystems is brewing on one of the largest web2 platforms on the planet.

After a period of speculatory frenzy, interest in trading these NFTs dwindled. Most of these assets are claimed for aesthetic purposes or out of curiosity. Remember the $500 figure I quoted above for the average size of an NFT trade on Ethereum? For this collection, it is down to $100.

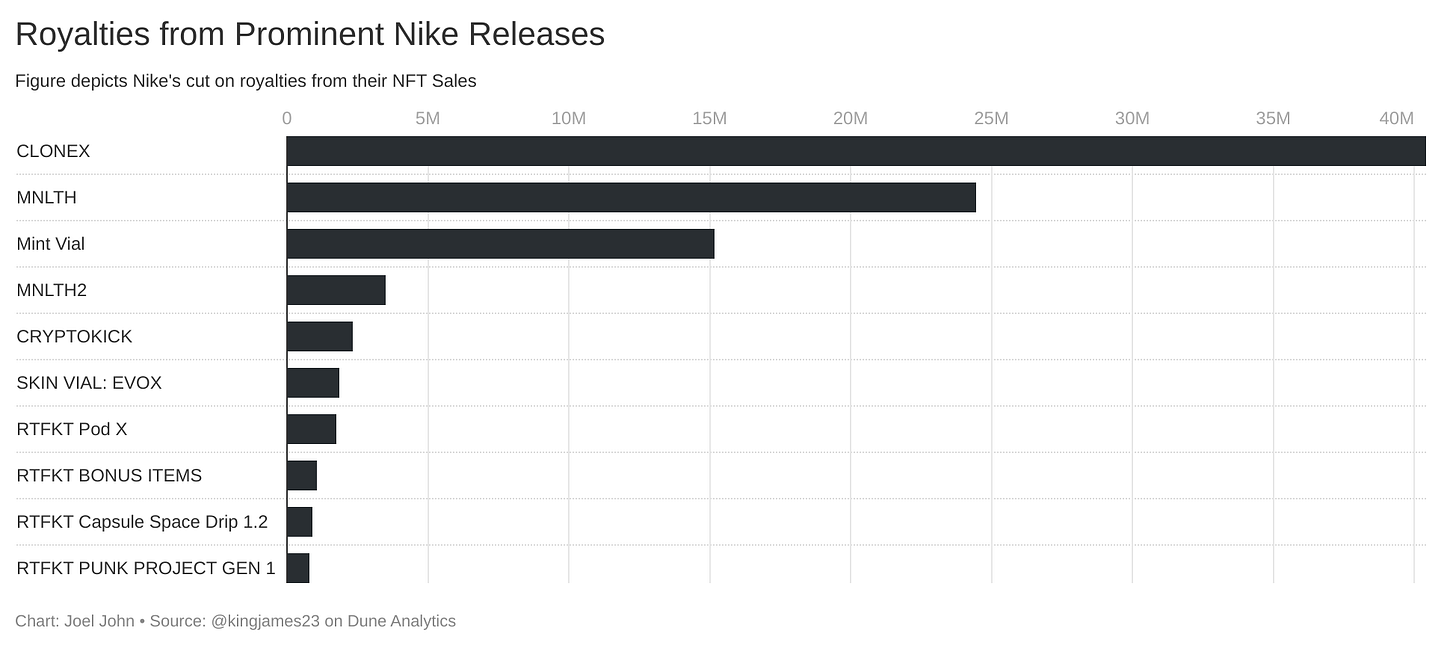

NFTs have served as speculatory instruments that appeal to a small subsection of the internet. And they have had a boom and bust cycle, but it is unlikely they will remain that way. What may happen instead is that they evolve to be crucial tools for identifying, tracing and interacting with users at a global scale in a permissionless way. By verifying which user has purchased a ticket meaningfully, played a specific game, or attended a particular event, we will unlock new use cases that were previously impossible. We are seeing early variations of this with a few brands like Nike.

At its crux, Nike’s strategy combines the brand’s distribution network, its existing suite of digital apps and Web3 to create ~$1 billion in additional revenue for the firm over the year. The royalties from those trades alone come to ~$100 million. They release “crates” from time to time which can be redeemed for limited edition sneakers. The Web3 component takes sneaker collecting to a whole new level. Firstly, anybody in the world can collect or trade these NFTs.

The market size is wider than a handful of cities. Secondly, Nike makes money any time somebody trades these NFTs, depending on whether they see a particular sneaker’s traits as desirable. Third, it opens up the possibility for digital assets to be embedded in digital environments in the future. Imagine a Nike NFT in Fortnite”

There’s still room for retail adoption of NFTs to surge on similar platforms, like Twitter and Instagram. For example, Instagram launching marketplaces and direct subscription products in the app would mean creators would develop digital-first collectables they can sell to their audience. They already allow creators to sell NFTs to their followers directly.

You get where I’m going. While volume for these instruments has declined – the user base, distribution outlets and the complexity of business models around NFTs have evolved substantially over the last few years. If anyone had suggested Instagram would embed NFTs in the product or that ~2% of Reddit’s user base may have NFTs in 2020, we would have thought they were stupidly optimistic. And yet, here we are in 2023, watching some of the biggest Web2 platforms adopt NFTs and calling it the end of days.

I could discuss our work with DAOs, Zero Knowledge Proofs, scaling, bridging, on-ramps and onboarding. But it would be a futile intellectual exercise that does not add to the underlying story I am trying to deliver here. Like all emergent technologies, Crypto ebbs and flows through periods of rapid adoption and bubble-like behaviour. Because it is simultaneously an emergent technology, a cultural shift and an asset class, it is as much a home to the artist as it is to the developer, the speculator, the anthropologist and, well, the guy just trying to get his money across the border without his tyrannical government laying claims to all of it.

There were years of work behind DeFi, NFTs and stablecoins before the latent interest in the sector became an actual user base. In the absence of that effort and commitment through the bear market of the last cycle, it would have been fair to suggest that all of Crypto is an industry of larps and that the technology has little meaningful to offer.

But that is not the case. The industry has grown 100 times in adoption on multiple parameters over the past three years. To suggest the industry is dead because liquidity is in decline is akin to saying a forest is dead because fall is here and the trees’ leaves are withering. To understand why the industry is alive and well, despite the collapse in price, we must look at how technological cycles have worked historically.

Zooming Out

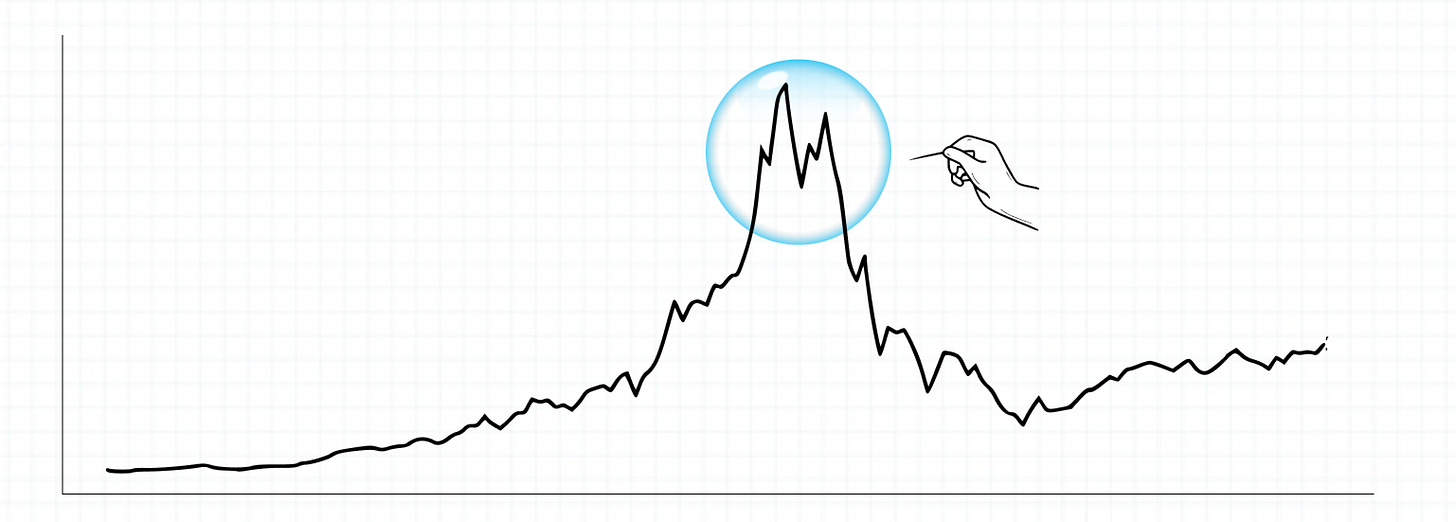

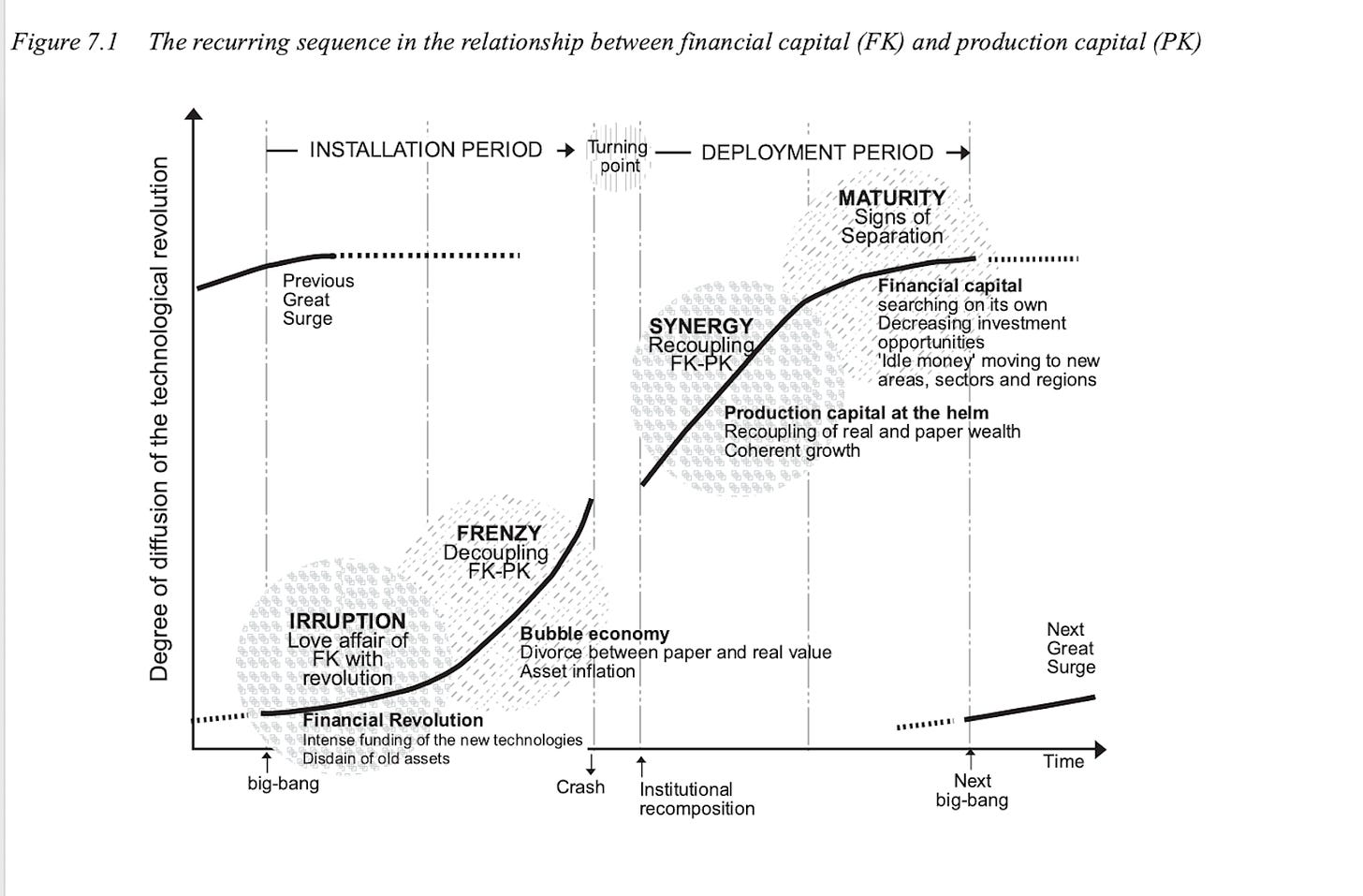

My thesis is that we just got out of a frenzy in crypto. It is not the end of days. It is a transition period that will bring much-needed maturity to our industry. When researching this piece, I stumbled across Carlota Perez’s Technological Revolutions and Financial Capital early on. Ben Thompson has written a full-fledged article on the book here. It gives a good lens on the relationship between institutions, technology and capital.

At its crux, the book argues that all technologies undergo an S-curve over time. An initial big bang usually occurs at the tail end of an existing paradigm coming to an end. In the context of crypto-native payments, we can consider traditional payment rails (like Visa) being disrupted by newer entrants (like USDC). This early stage of the market generally needs more interest from the mainstream. It is when the early adopters set up their base and work together on sound principles: for the love of the technology and the problems it can solve.

As time passes, there is a decoupling between reality and what technology can offer. This period of ‘ballooned” expectations sets the stage for a bubble. Financial capital takes on increasing risk with hopes of being early to a paradigm shift. But people generally get a few things wrong. Early on, they overestimate what possibilities new technology can offer. Later, it is faulty timeline assumptions for the technology to be adopted. Ben Thompson and Carlota Perez have varying views on where crypto sits in this equation. Sidenote: Carlota Perez shared her opinions on where blockchains stand in this equation in this video.

An incredible amount of fatigue in capital deployment generally marks the tail end of a frenzied stage. This is generally due to a lack of returns from existing investments. Combine that with debt defaults that emanate from capital given out during an era of easy money. You will see a point when capital infusion contracts but technological capabilities expand. Put differently, the amount of money required to add a unit amount of value to the user reduces. This changing unit economics sets the stage for an emergent technology to be embraced.

Ironically, we have seen multiple aspects of the factors mentioned above play out. As I write these words, the Winklevii (thats a pun, not a typo) brothers are writing open letters to Barry Silbert, hoping to recoup capital. That is bad debt in action. Due to their bad investment record, multiple VC funds will likely be forced to shut shop in the next six months. SAFTs will trade in secondary markets for pennies on the dollar. Talent will become more affordable for enterprising founders that stick around, and the public consensus that the industry is dead will mean only people that genuinely care about the possibilities of the technology will stick around. That gap – between a period of frenzy and synergy – is where opportunities lie.

I hate using the word synergy. It feels contrived. But it’s the terminology in Carlota Perez’s work. So bear with me as I use it. Multiple things make it feel like we are at the cusp of synergy. Firstly, the lack of venture capital dollars in the industry would mean existing enterprises could likely acquire many startups for pennies on the dollar. This would solve labour and intellectual property deficits in a cost-efficient way. Secondly, large web2 organisations like Meta, Google, Microsoft, and AWS have each tinkered with blockchains and developed their own offerings.

In the early stages of a technology, it makes sense for incumbents to keep new entrants at a distance. Corporations like JP Morgan invest in them to maintain exposure, but their reputation is not affected if there is a colossal failure. The FANGs have played Web3 like this. So have the banking behemoths. Retail outlets? Same. Even the gaming studios like Ubisoft have built exposure to the sector with a similar philosophy.

Secondly, a sober period will come in the next few quarters where building things people want will matter more than ever. With VCs no longer rushing to deploy capital into new ventures, founders must focus on the lifeblood that keeps all startups worth pursuing: cash flow and scale. More importantly: cash flow from people who find the things we build useful.

After every technological bubble in history, there comes a period where regulators are quick to action. After the South-Sea bubble of the 18th Century, the British Government issued the Bubble Act. It forbade individuals from launching joint-stock companies unless approved by the Royal Charter. The Dodd-Frank act came right after the crisis of 2008. It is safe to think regulators will be more proactive than ever in the coming year. Given the number of retail users that have lost money in the past year, it is also likely that crypto and web3 will be a “political matter”.

It may seem like the end of the industry, and there will be panic all around. But the clarity offered by regulators will open up the doors for a new generation of ventures to be built to the standards the industry needs. There is a historical precedent for this. In 2014, when Mt Gox collapsed in a massive hack, one had every reason to think the industry was done for good. But the regulations from that painful experience insulated users in FTX Japan. Last week, they made it possible for users to withdraw their assets.

What’s Next

Has crypto failed? I don’t think so. The simple argument against it is that as long as Ethereum and Bitcoin are processing transactions, these primitives are doing what they were designed to do. But if I were to suggest we have reached the pinnacles of human progress, that would be a cruel joke. And we have made sufficient jokes out of ourselves in the past few years. Between the random yield farms, the multiple forked clones of the same thing, the quick VC unlocks, the rush to buy ugly art, the arrogant founder and the starry-eyed employees working four hours a day with him – all features of a market in a frenzy.

While we must admit that there were excesses, it is just as necessary to understand that we have made an incredible amount of progress. Bubbles are a feature, not a bug. Human excitement is a necessity. They enable investors that took the risk in crashes (like the one we are in now) to exit meaningfully whilst bringing in public interest towards emergent technologies. There is no multiverse where crypto – or drones, AI or vertical farming – embed in human society at scale without heightened expectations and excessive investing.

It is easy to suggest that web3 is a market of speculators and that the tools we build don’t matter outside. But it ignores that all technologies are speculative in their early stages. The railways, bicycles, telephones, internet and shipping companies have had bubbles in their early phases. And much like crypto today, people lost their savings and livelihoods. What follows eventually is a period of market maturity—a time when sober minds collaborate on meaningful things. If we were to write off the internet in the mid-2000s due to the dot-com bubble, we’d never see the trillions in the economic output it has enabled in the decade that followed.

What may happen, in my view, is that the level of tolerance for trash would reduce drastically. Founders, investors and employees will work with an increasing focus on the numbers that matter – users, revenue, and margins. Unit economics will become cool again. As it inevitably happens, markets will filter out the clowns as the circus winds down. When the technology reaches maturity, we will no longer refer to the use of blockchains as “web3”, like A16z calls it.

Instead, as we have seen through Instagram, Twitter and Reddit – these primitives would embed in existing experiences. Nobody refers to calling an uber Uber as using a global positioning system and telecommunication to request drivers in immediate proximity for transportation. We call it – taking an uber. Or Googling. Or texting. The technology becomes redundant to the point where it’s referred to as a verb. So long as teams can deliver experiences that matter to the average user – we have something to build towards.

When writing this piece, I could not help but think of the Wright brothers. The first flight was a few hundred feet long. Almost redundant in that you would rather walk that distance than sit on metal wings strapped to a loud engine. Blockchains are somewhat similar. Clunky and almost redundant. But in less than 70 years since that initial flight, we stepped foot on the moon. All technologies follow a similar arc.

Maybe, we should not obsess over how short these flights are and miss out on literally making it to the moon. All pun aside, I leave you with this incredible bit of wisdom from an (alleged) former hedge fund mogul turned (alleged) travel influencer.

This article has been written and prepared by the Joel, in collaboration with editorial inputs from – Benjamin Hoffman, Lisa Dawson, Denny Dien, Alicia Kenworthy and Kym Ellis. Committed to staying current with industry developments and providing accurate and valuable information, GlobalCoinResearch.com is a trusted source for insightful news, research and analysis.

Disclaimer: Investing carries with it inherent risks, including but not limited to technical, operational and human errors, as well as platform failures. The content provided is purely for educational purposes and should not be considered as financial advice. The authors of this content are not professional or licensed financial advisors and the views expressed are their own and do not represent the opinions of any organization they may be affiliated with.

*****

-

“Institutional Aping” great header lmao. Nice read.