A Legal Engineer’s Guide to a “Fair Launch”

Case Study #4?—?SushiSwap aging like a fine wine

By James McCall, Love agriculture, finance, and law Not legal advice. DAO things w/ @lex_dao @farmapper

Join the Global Coin Research Network now and contribute your thoughts!

If you’d like to learn about crypto, join our Discord channel and be kept up to date with the latest investment research, breaking news and content, Crypto community happenings around the world!

After a delay to explore our enumerated rights under the US Constitution, we backtrack to explore fair launches and food fights. This case study has all the betrayal and intrigue of an episode of Game of Thrones with, at times, the same stench. Starting as another food fork, SushiSwap was pitched as a “community-owned” Uniswap fork. Uniswap v2 is an open source project that is an automated market maker “AMM” which is a decentralized exchange that allows the swapping of tokens between a pair. The provider of the token pair (the “liquidity provider) accrues rewards necessary to compensate for allowing their pooled capital to be available. The liquidity pool is available for traders to swap tokens between the pair and the “swappers” pay a fee to the liquidity providers for accepting the risk and opportunity cost associated with providing the capital.

SushiSwap’s anonymous team started its project with the innovative approach of copy/pasting the Uniswap project and front end into a food dejure project called SushiSwap. This fork of the code and front end of Uniswap spawned a competitor to Uniswap which is one of the largest building blocks on Ethereum. Uniswap accomplished their market position without having a token (UNI was issued on September 16, 2020) or any fees from the protocol going to the developer. For each token swap on Uniswap the fee of 0.3% goes to the pool for those providing the liquidity. The Uniswap developer team raised relatively small amounts (compared to ICO craze) from VC rounds and it is speculated that there will be a monetization strategy with Uniswap v3 or perhaps through UNI governance. The Uniswap project code itself is open source, so this forking activity is perfectly legal as recently illustrated by Hayden Adams the Uniswap founder. But debates over what is legal and what is ethical continue at pace.

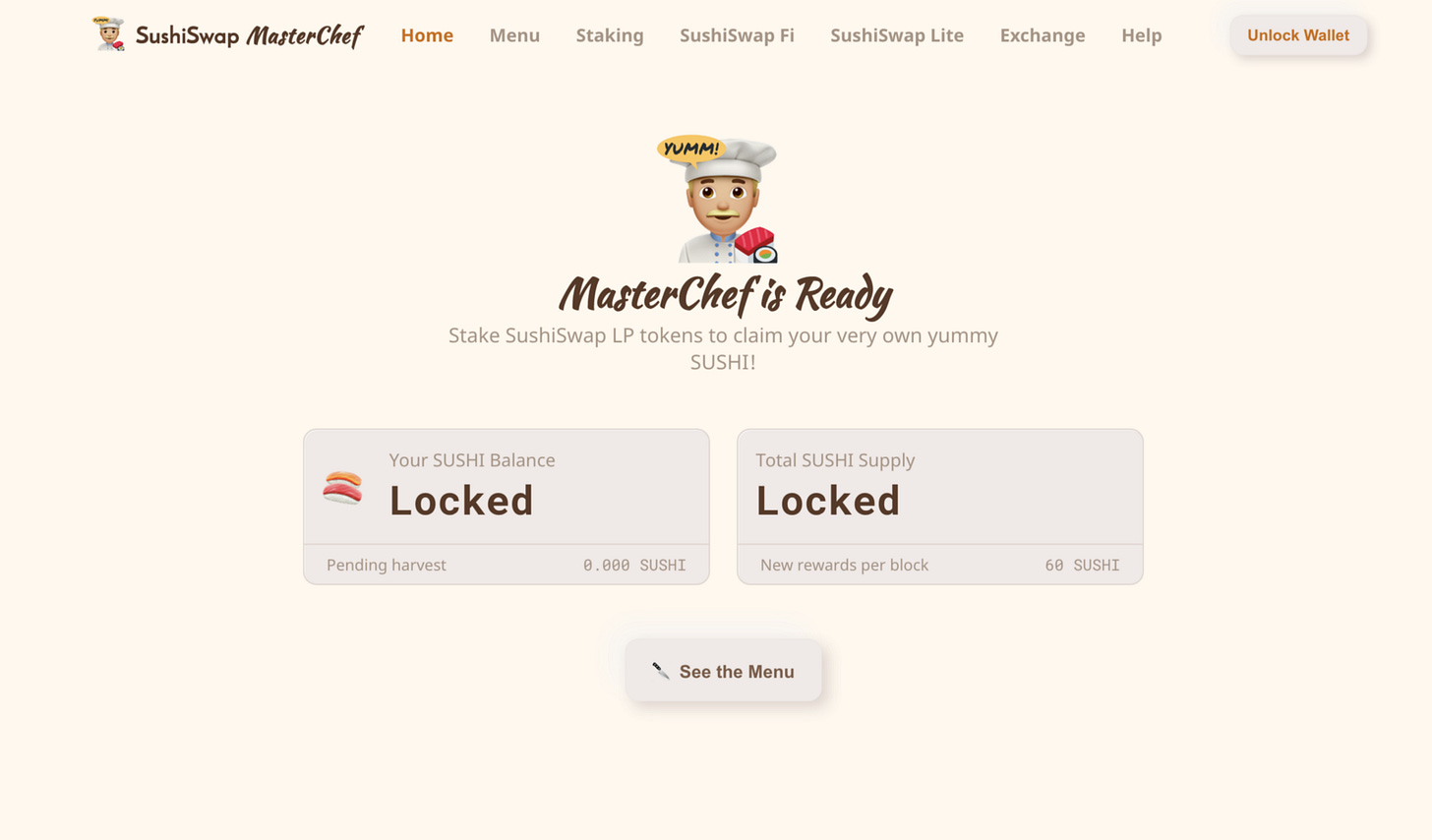

SushiSwap was pitched as a “community” that can innovate around and solve immediate issues through a community owned ($sushi) DEX. The farming of $SUSHI tokens was not built around individual tokens, but actually through “staked” liquidity pool tokens on Uniswap. In other words, when a liquidity provider enters the ETH —DAI pool on Uniswap, they are returned a Uniswap pool token for the pooled ownership amount of that liquidity pool which itself is a separate ERC-20 token. The Sushi farming allowed the “staking” of these pooled tokens to earn a $SUSHI token similar to $YAM, $COMP, $YFI, etc. The rewards were accelerated at 10x during the first two weeks of the project and grew to over a billion dollars in value staked to earn the $SUSHI rewards.

A major difference between Uniswap and Sushiswap is the different incentives. The $SUSHI token is a governance coin that is also meant to share in a portion of liquidity provider fees that are traded on SushiSwap. The forked successor to Uniswap made one very notable difference and that was to split the swap fee (of 0.30% on Uniswap) with 0.25% to the liquidity provider and 0.05% going to the $SUSHI token holder. It remains to be seen whether this will naturally incentivize liquidity providers properly and organically or whether it will require a stream of inflationary rewards to keep the liquidity providers in Sushiswap versus other on chain AMM pools.

This forking of code, community, and liquidity through attempting this was coined a “vampire attack” against Uniswap by incentivizing moving liquidity providers to SushiSwap through a migration smart contract. Not sure if vampire attack is quite correct, as everyone knows that vampires turn their host into vampires. But a tapeworm attack™ has yet to catch on in the wider fair launch token community.

- Step 1 was to pool actual Uniswap token pairs and earn $SUSHI?—?the vampire attack to suck liquidity out of its host

- Step 2 was to incentivize liquidity through Uniswap pair $SUSHI?—?ETH

- Step 3 was to hope everyone stayed staked to follow the migration over to the competing product SushiSwap once the 10x rewards period ended

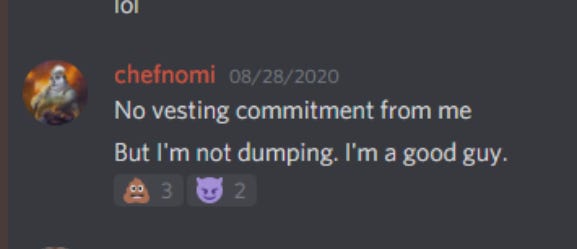

Unlike Andre Cronje from YFI, SushiSwap was started by an anonymous founder or team with the handle “ChefNomi” with a Panda memed card as “his” avatar. The $SUSHI economics also had a “developer” pool of 10M Sushi tokens which was for future development of the protocol. Chef Nomi was mercurial and difficult to pin down on common sense protections to protect the ecosystem. When asked about the devshare, ChefNomi said, “IN THEORY I CAN SELL ALL OF THEM, BUT I DON’T SEE ANYTHING WRONG WITH IT. IT’S THE DEVSHARE AND IT’S BEEN SPECIFIED IN THERE SINCE THE BEGINNING.” Chef Nomi.

- Chef Nomi would not agree to having a multi sig control the contracts or the development fund

- SushiSwap did not launch with a disclosed audit, just a demand to audit as it became too large to fail.

- Would not commit to a vesting schedule or timelock on the tokens.

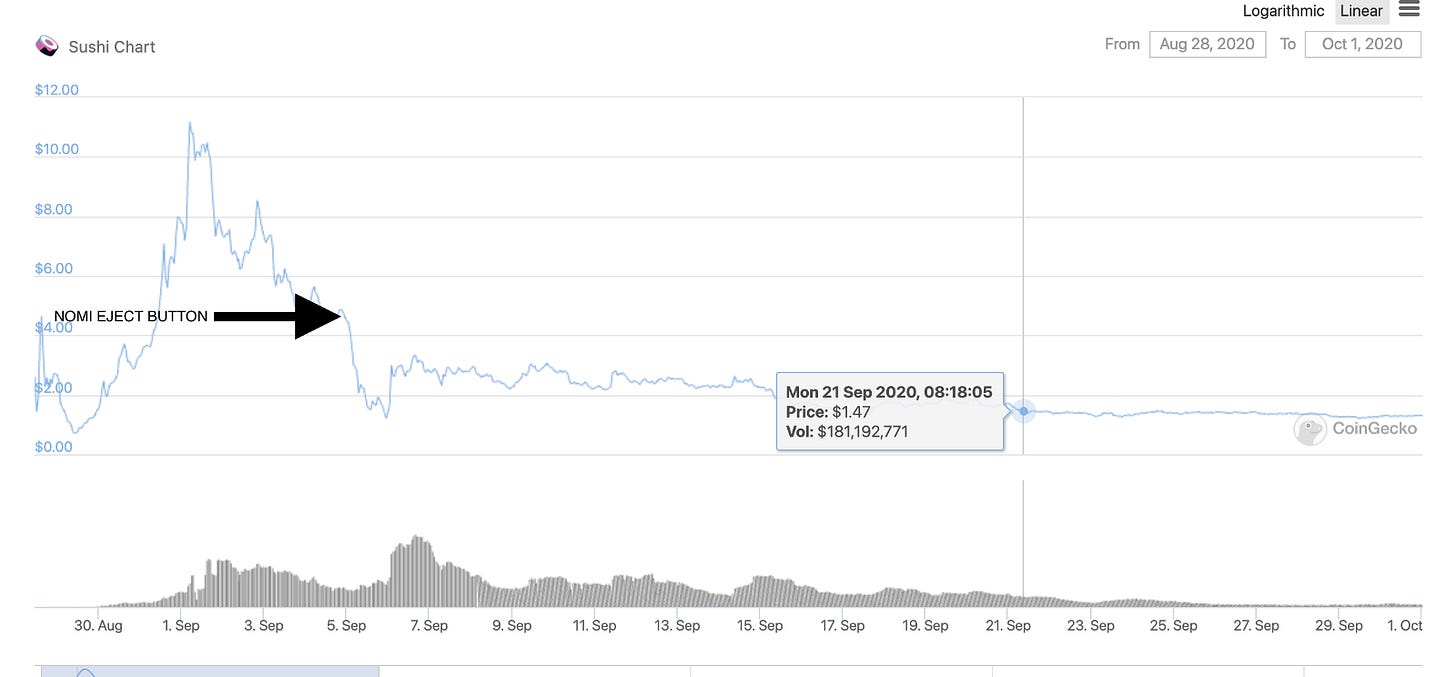

So, we made the point earlier in this series that liquidity is the lifeblood of these token projects. With SushiSwap there was an incentivized pool to provide both $SUSHI and $ETH tokens in the liquidity pool. This pool filled up and increased with the popularity of the $SUSHI token farm. The “Pool 2” is meant to incentivize the liquidity providers for the very volatile and uncertain period of price discovery. But, on one random morning the developer decided to drain the whole devshare fund by selling $SUSHI for ETH against the “incentivized pool”.

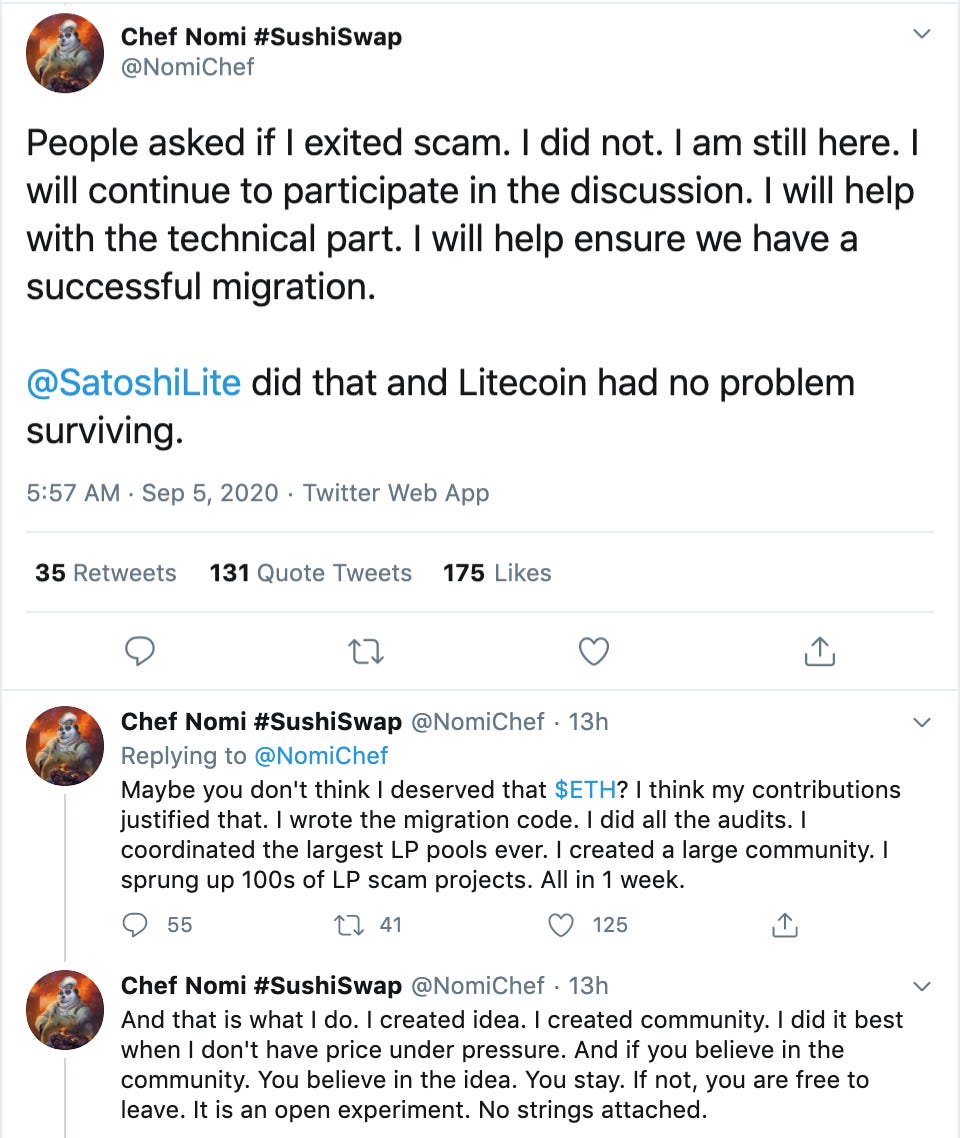

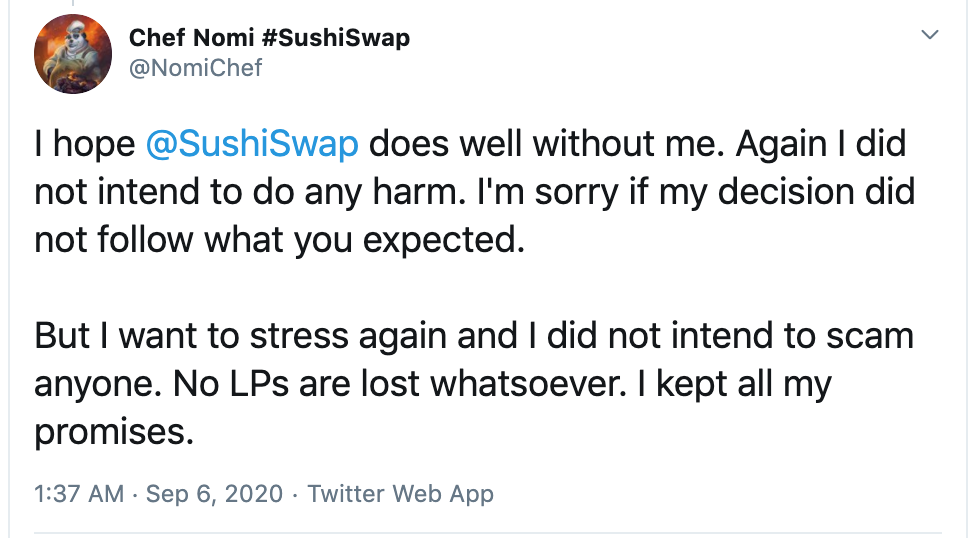

The impact was a community revolt and huge token sell off. Chef Nomi walked with millions in ETH for doing what seemed like very little work, especially “original” work. But through pressure (legal, criminal, social) Chef Nomi on September 11, 2020, returned the amounts obtained in ETH for the Sushi community to use for protocol development and rewards and agreed to transfer multisig to other parties.

Was $SUSHI dump a crime? A securities violation? It certainly wasn’t “fair” or honest.

There could be a novel written and investigated about the Sushi saga as it has most aspects of a Shakespearean play. Plenty of comedy mixed with tragedy. But despite calls from cryptolaw twitter for legal recourse and lawyering up there are positives to be learned without running at the first moment to a lawsuit. For many, Ethereum is an experiment in self governance and self regulation. Can self governance and self regulation work?

The clear insinuation from Chef Nomi that he wouldn’t dump the token, that he was a “good guy”, could have been reasonably relied upon where the liquidity providers would have thought that the developer would not dump into the pool and exit. What harm was done and who got hurt? Here a list of questions and observations.

- Sushi holders always knew that the tokens held were not time locked and could be dumped against the $SUSHI-ETH pool at any time. The disclosures were made, in the code, and by Chef Nomi himself. People should be disappointed but not really surprised. Providing the liquidity to a pair, the liquidity provider is both the entrance liquidity and the exit liquidity. This is the “work”.

- Does the firing of the ammo with the elimination of the devshare remove the “known unknowns” of when the Chef Nomi devshare gets dumped? There was always going to be the overhang of when the developer share would be dumped on the market, perhaps better to just get it over with. The same trade off is intrinsic in most vc backed projects, stocks, etc. They have vesting periods, and windows, that are tracked by astute investors, but they will often be “dumped” all the same. The hangover just came early with Sushiswap.

- What are the damages and how would they be calculated? These fair launch tokens may or may not be the type of “sufficiently decentralized” securities that the SEC wants to regulate, but if they do, how would damages be assessed and whom against? Obviously if Chef Nomi could be tracked down, and the funds recovered, and if they are even in a US jurisdiction, then who would get the recovery besides the lawyers? Surely there are those that can prove they market bought $SUSHI, or conversely put good ETH into the liquidity pool that they were sold against. So, the law is messy but is ultimately decent at inventing ways to balance the equities.

- Is it more decentralized now that the tokens from the Chef Nomi whale are out in the wild? In other ways, does the distribution from the dump make $SUSHI look less like a security? The developer is as GONE as Satoshi. Obviously, if anyone relied on Chef Nomi, are they going to rely on Chef Nomi anymore? Did the rug pull, somehow lead to a more decentralized community less reliant on Chef Nomi? Is the reliant party just replaced with another, enter SBF? it should be noted that $SUSHI has recovered nicely since the the return of the $SUSHI spoils.

The above prompts are just for discussion purposes and are not meant to carry any further connotation. Arguments are funny as there are always counter arguments. No war plan survives after the first shots are fired. However SushiSwap drama shakes out, regulating farm coins is going to be a different and challenging beast. Hopefully legal and compliant governance procedures for “exit to community” projects can develop over time as this does appear to be a interesting and oddly efficient manner in launching projects, forming capital similar to a direct listing, and bootstrapping some sort of protocol governance to the project.

UNISWAP V SUSHISWAP

It is interesting to note that as of the date of this article the $SUSHI project has continued to evolve, iterate and innovate. Oddly criticism has been pointed at the tapeworm attack victim Uniswap of late, for being slow, and closed to the Ethereum community at large.

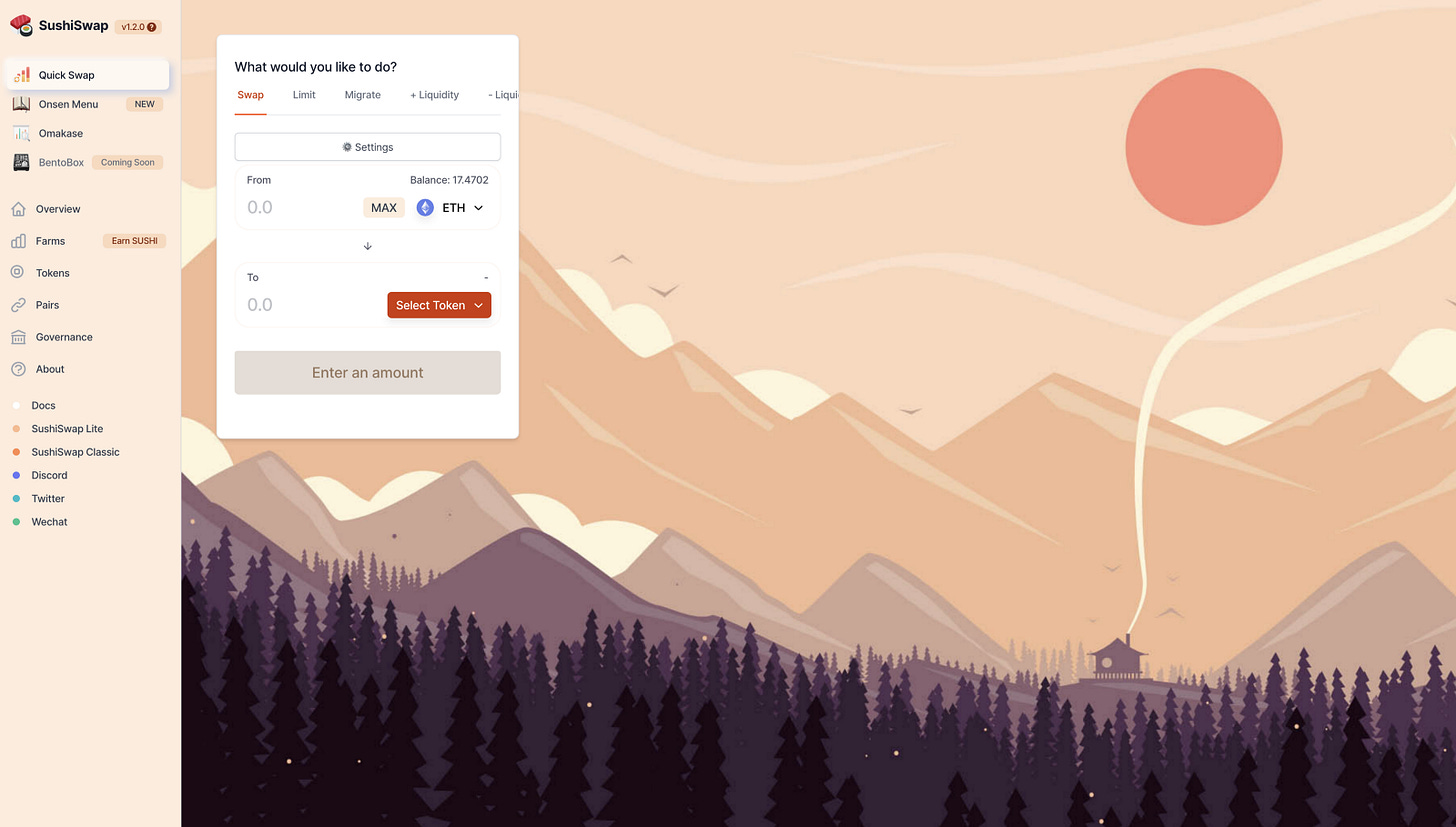

SushiSwap innovation has happened at a rapid pace. Early assessment is that for the average user, the competition is a real positive as developers and protocols battle in the arena for liquidity providers and volume. Sushiswap.fi has added much clamored for features, limit orders, curated lists of farming opportunities, bento box, snapshot governance, etc.

Special thanks to Ross Campbell for providing comments. Next case study to follow will probably be PERP but may turn it over for a LEX vote, stay tuned…..

All links provided are for informational purposes only and not meant as recommendations of the people or products. Nothing herein is legal or financial advice and should not be relied upon without reaching out to your own personal attorney. The linked ABA disclaimer is appended to the blog.

LexDAO is a non-profit association of legal engineering professionals that brings the traditional legal settlement layer to code, and coded agreements to the masses. We believe that everyone deserves access to justice provided in a quick and efficient manner. If legal services were easier to use, verify, and enforce, we could live in a fairer world. Blockchain technology offers solutions to many problems in the legal space. Our mission is to research, develop and evangelize first-class legal methods and blockchain protocols that secure rules and promises with code rather than trust. We do this by training LexDAO certified legal engineers and building LexDAO certified blockchain applications. We strive to balance new deterministic tools with the equitable considerations of law to better serve our clients, allies, and ultimately citizens.

To be continued…..